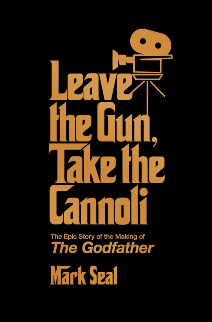

There are six books on my shelves about the making of The Godfather: The Godfather Family Album, The Official Motion Picture Archives, The Annotated Godfather, The Godfather Notebook, The Godfather Book, and now Mark Seal’s Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of ‘The Godfather’. As Seal acknowledges in his preface, “The Godfather has spawned its own massive field of study, a trove of books, articles, documentaries...” Some familiar production anecdotes are inevitably duplicated throughout these six books, though each title also provides ample original material, and each has a different approach to the making of the film.

What distinguishes Seal’s new book? Firstly, it has an extended interview with Francis Ford Coppola (who admits that, “at the root of it all, I was terrified”). Also, one chapter quotes extensively from a stenographer’s transcript of a six-hour pre-production meeting. This document is a valuable primary source, as it accurately records exactly what was said at the time, such as Coppola’s explanation of the film’s opening line: “Just starting with, ‘I believe in America,’ because it’s what the whole movie is about.” Previously, Seal wrote a Vanity Fair article on the making of the film for the magazine’s 2009 Hollywood issue, and an oral history of Pulp Fiction for the 2013 Hollywood issue.

What distinguishes Seal’s new book? Firstly, it has an extended interview with Francis Ford Coppola (who admits that, “at the root of it all, I was terrified”). Also, one chapter quotes extensively from a stenographer’s transcript of a six-hour pre-production meeting. This document is a valuable primary source, as it accurately records exactly what was said at the time, such as Coppola’s explanation of the film’s opening line: “Just starting with, ‘I believe in America,’ because it’s what the whole movie is about.” Previously, Seal wrote a Vanity Fair article on the making of the film for the magazine’s 2009 Hollywood issue, and an oral history of Pulp Fiction for the 2013 Hollywood issue.