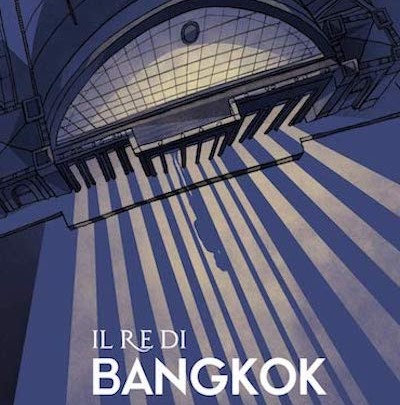

The graphic novel Il Re di Bangkok (‘the king of Bangkok’), was published in Italian last year, and has now been translated into Thai. The book was written by Claudio Sopranzetti and Chiara Natalucci, with illustrations by Sara Fabbri. (The Thai edition has been self-censored — on pp. 93, 157, and 205 — though the Italian edition is unexpurgated.)

The title character, Nok, is a blind lottery-ticket vendor from Isan who travels to Bangkok for a better life. Economic migration from upcountry to the capital is commonplace, and was a standard theme of politically-conscious writers and directors in the mid-1970s. Nok becomes increasingly politically engaged during his time in Bangkok, as he lives through the 1992 ‘Black May’ massacre, the ‘tom yum kung’ economic crisis, the rise and fall of Thaksin Shinawatra, the 2006 coup, and the red-shirt protests. The book ends as the red-shirts are massacred by the military, an event that took place exactly a decade ago.

For its Thai publication, Il Re di Bangkok was retitled ตาสว่าง (ta sawang), a term describing the sense of political awakening experienced by Nok. Several of the Thai filmmakers interviewed for the forthcoming book Thai Cinema Uncensored have explained their own feelings of newfound political enlightenment: Pen-ek Ratanaruang (“somebody like me, who five years ago had no interest in politics at all”), Yuthlert Sippapak (“I never gave a shit about politics. But right now, it’s too much”), Chulayarnnon Siriphol (“I turned to be interested in the political situation”), Thunska Pansittivorakul (“I started to learn about politics”), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (“I was politically naïve”), and Nontawat Numbenchapol (“I was a teenager, a young man not interested in politics so much”) all discussed their personal experiences of ta sawang.

The title character, Nok, is a blind lottery-ticket vendor from Isan who travels to Bangkok for a better life. Economic migration from upcountry to the capital is commonplace, and was a standard theme of politically-conscious writers and directors in the mid-1970s. Nok becomes increasingly politically engaged during his time in Bangkok, as he lives through the 1992 ‘Black May’ massacre, the ‘tom yum kung’ economic crisis, the rise and fall of Thaksin Shinawatra, the 2006 coup, and the red-shirt protests. The book ends as the red-shirts are massacred by the military, an event that took place exactly a decade ago.

For its Thai publication, Il Re di Bangkok was retitled ตาสว่าง (ta sawang), a term describing the sense of political awakening experienced by Nok. Several of the Thai filmmakers interviewed for the forthcoming book Thai Cinema Uncensored have explained their own feelings of newfound political enlightenment: Pen-ek Ratanaruang (“somebody like me, who five years ago had no interest in politics at all”), Yuthlert Sippapak (“I never gave a shit about politics. But right now, it’s too much”), Chulayarnnon Siriphol (“I turned to be interested in the political situation”), Thunska Pansittivorakul (“I started to learn about politics”), Apichatpong Weerasethakul (“I was politically naïve”), and Nontawat Numbenchapol (“I was a teenager, a young man not interested in politics so much”) all discussed their personal experiences of ta sawang.