The Right to Rule: Thirteen Years, Five Prime Ministers and the Implosion of the Tories, by Ben Riley-Smith, sets out to explain how the Conservatives have held on to power in the UK since 2010. One reason is simply that the party has an inbuilt sense of entitlement: “The story that emerges is one of a party built to rule. Time and again, the same message was echoed by interviewees: what must be understood is that the Conservatives are not an ‘ideological party’ but a ‘power party’.”

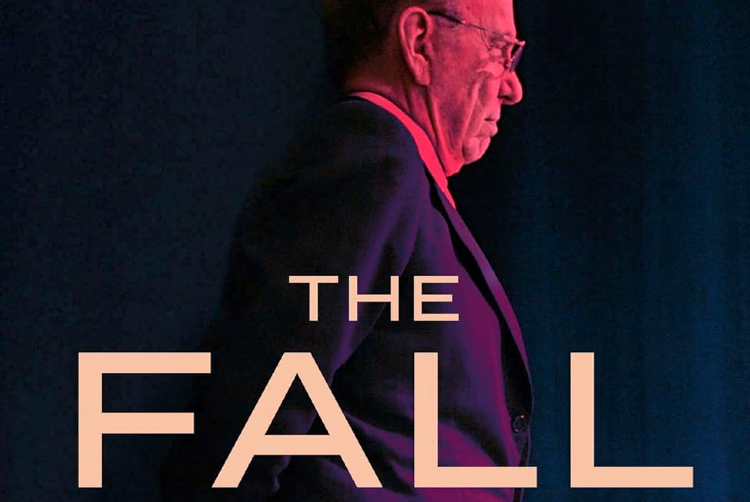

A complete political history of the past thirteen years would be impossible to cover in a single volume, so the book instead focuses on “ten critical moments or parts of the story, the pivotal points that explain the wider whole.” These include David Cameron’s decision to hold the Brexit referendum, Theresa May’s ill-fated 2017 election, Boris Johnson’s resignation (Riley-Smith subscribes to the ‘three Ps’ theory cited in The Fall of Boris Johnson), and the brief Liz Truss premiership.

Riley-Smith interviewed more than 100 sources for the book, including three of the last five prime ministers (Cameron, Johnson, and Truss). He spoke to twenty of Johnson’s cabinet ministers, and obtained the first drafts of Johnson’s resignation speech and Truss’s party conference speech. He also quotes previously unpublished material from his Telegraph interview with Sunak—“people are fed up with politicians talking about things and not actually doing them”—and extracts from a tranche of internal party memos from the 2017 election campaign.

Surprisingly, The Right to Rule has not been widely reviewed, except by The Daily Telegraph, of which Riley-Smith is the political editor. But it deserves wider coverage, particularly for its revealing insights into Conservative party procedures: it explains the process by which letters of no confidence are submitted to the chairman of the 1922 Committee, and it includes the first published photograph of a cabinet reshuffle whiteboard.

A complete political history of the past thirteen years would be impossible to cover in a single volume, so the book instead focuses on “ten critical moments or parts of the story, the pivotal points that explain the wider whole.” These include David Cameron’s decision to hold the Brexit referendum, Theresa May’s ill-fated 2017 election, Boris Johnson’s resignation (Riley-Smith subscribes to the ‘three Ps’ theory cited in The Fall of Boris Johnson), and the brief Liz Truss premiership.

Riley-Smith interviewed more than 100 sources for the book, including three of the last five prime ministers (Cameron, Johnson, and Truss). He spoke to twenty of Johnson’s cabinet ministers, and obtained the first drafts of Johnson’s resignation speech and Truss’s party conference speech. He also quotes previously unpublished material from his Telegraph interview with Sunak—“people are fed up with politicians talking about things and not actually doing them”—and extracts from a tranche of internal party memos from the 2017 election campaign.

Surprisingly, The Right to Rule has not been widely reviewed, except by The Daily Telegraph, of which Riley-Smith is the political editor. But it deserves wider coverage, particularly for its revealing insights into Conservative party procedures: it explains the process by which letters of no confidence are submitted to the chairman of the 1922 Committee, and it includes the first published photograph of a cabinet reshuffle whiteboard.