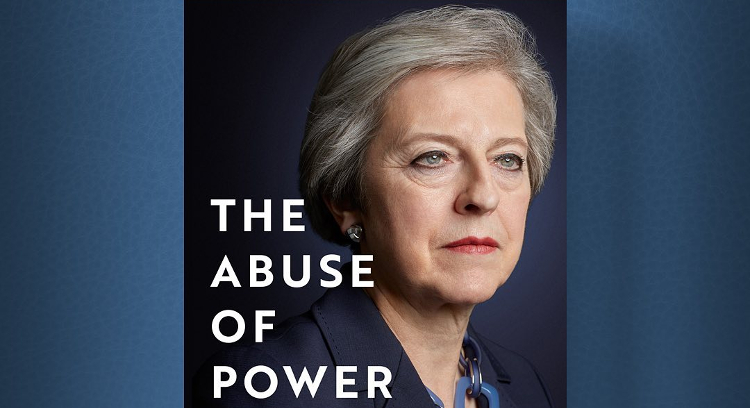

The prime ministerial memoir is a staple of British political literature. Recent PMs Tony Blair (A Journey), Gordon Brown (My Life, Our Times), and David Cameron (For the Record) have all written about their times in office, though Theresa May’s new book isn’t a traditional memoir. May also makes clear that it’s “not an attempt to justify certain decisions I made in office or to provide a detailed retelling of historical events.” Instead, it’s an account of “the abuse of power exhibited so often in the way the institutions of the state, and those who work within them, put themselves first and the people they are there to serve second.”

The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life includes damning assessments of the Hillsborough Stadium and Grenfell Tower tragedies, and the Primodos scandal, amongst other miscarriages of justice (but not the Post Office Horizon case). May rightly condemns the institutional failings that resulted in these horrific episodes, though her book also discusses seemingly unrelated issues, including her government’s Brexit negotiations. May’s reflections on Brexit — and her thoughts on other world leaders, such as Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin — are fascinating, though they would be more suited to a conventional memoir. In fact, there’s something quite offensive about equating the Brexit deadlock with the Hillsborough disaster.

(On stage at the 2018 Brit Awards, Stormzy asked: “Theresa May, where’s the money for Grenfell?” His single Vossi Bop, released in 2019 when May was PM, featured the line “Fuck the government and fuck Boris”, a few months before Boris Johnson replaced May as prime minister.)

As May recognises, she will be remembered primarily for her protracted Brexit negotiations: “I know in my heart of hearts that the political reality is that my premiership will always be seen in the context of Brexit and my failure to get a deal through the House of Commons.” She also accepts partial blame for the 2017 election campaign car-crash that wiped out her parliamentary majority: “The most obvious, and arguably the defining, mistake was the press conference after the revision of our social care policy where I said nothing had changed. Obviously something had changed.”

The election result greatly weakened May’s ability to pass legislation in parliament, though she blames former parliamentary Speaker John Bercow for the stalemate instead: “I am certain that he scuppered the Brexit deal.” May is surprisingly direct in her condemnation of Bercow: without mincing words, she describes him as “not just a bully but a serial liar.” She also criticises her predecessor as PM for the Downing Street parties held during coronavirus lockdowns: “there were those at the top of politics, including but not limited to Boris Johnson as Prime Minister, who did not think that the laws they made applied to them.”

In contrast, the book presents May as a vicar’s daughter and a dutiful crusader for justice. In her concluding chapter, May considers how to prevent future abuses of power, but rather than increased regulation or transparency, she calls for more public figures who share her belief in “[s]elf-sacrifice rather than selfishness.” But it’s unrealistic to expect such selflessness from those in public life (except perhaps Gordon Brown, who has a similar background to May), and the book’s final lines are overly idealistic: “those in public service, particularly politicians, should cast aside the mantle of selfishness and devote themselves unashamedly to duty and the service of others.”

The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life includes damning assessments of the Hillsborough Stadium and Grenfell Tower tragedies, and the Primodos scandal, amongst other miscarriages of justice (but not the Post Office Horizon case). May rightly condemns the institutional failings that resulted in these horrific episodes, though her book also discusses seemingly unrelated issues, including her government’s Brexit negotiations. May’s reflections on Brexit — and her thoughts on other world leaders, such as Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin — are fascinating, though they would be more suited to a conventional memoir. In fact, there’s something quite offensive about equating the Brexit deadlock with the Hillsborough disaster.

(On stage at the 2018 Brit Awards, Stormzy asked: “Theresa May, where’s the money for Grenfell?” His single Vossi Bop, released in 2019 when May was PM, featured the line “Fuck the government and fuck Boris”, a few months before Boris Johnson replaced May as prime minister.)

As May recognises, she will be remembered primarily for her protracted Brexit negotiations: “I know in my heart of hearts that the political reality is that my premiership will always be seen in the context of Brexit and my failure to get a deal through the House of Commons.” She also accepts partial blame for the 2017 election campaign car-crash that wiped out her parliamentary majority: “The most obvious, and arguably the defining, mistake was the press conference after the revision of our social care policy where I said nothing had changed. Obviously something had changed.”

The election result greatly weakened May’s ability to pass legislation in parliament, though she blames former parliamentary Speaker John Bercow for the stalemate instead: “I am certain that he scuppered the Brexit deal.” May is surprisingly direct in her condemnation of Bercow: without mincing words, she describes him as “not just a bully but a serial liar.” She also criticises her predecessor as PM for the Downing Street parties held during coronavirus lockdowns: “there were those at the top of politics, including but not limited to Boris Johnson as Prime Minister, who did not think that the laws they made applied to them.”

In contrast, the book presents May as a vicar’s daughter and a dutiful crusader for justice. In her concluding chapter, May considers how to prevent future abuses of power, but rather than increased regulation or transparency, she calls for more public figures who share her belief in “[s]elf-sacrifice rather than selfishness.” But it’s unrealistic to expect such selflessness from those in public life (except perhaps Gordon Brown, who has a similar background to May), and the book’s final lines are overly idealistic: “those in public service, particularly politicians, should cast aside the mantle of selfishness and devote themselves unashamedly to duty and the service of others.”