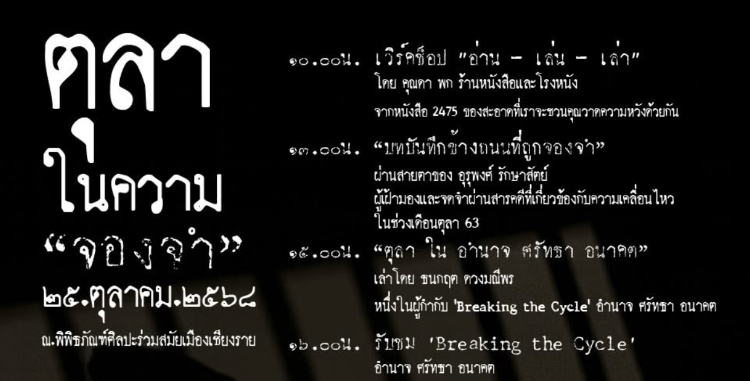

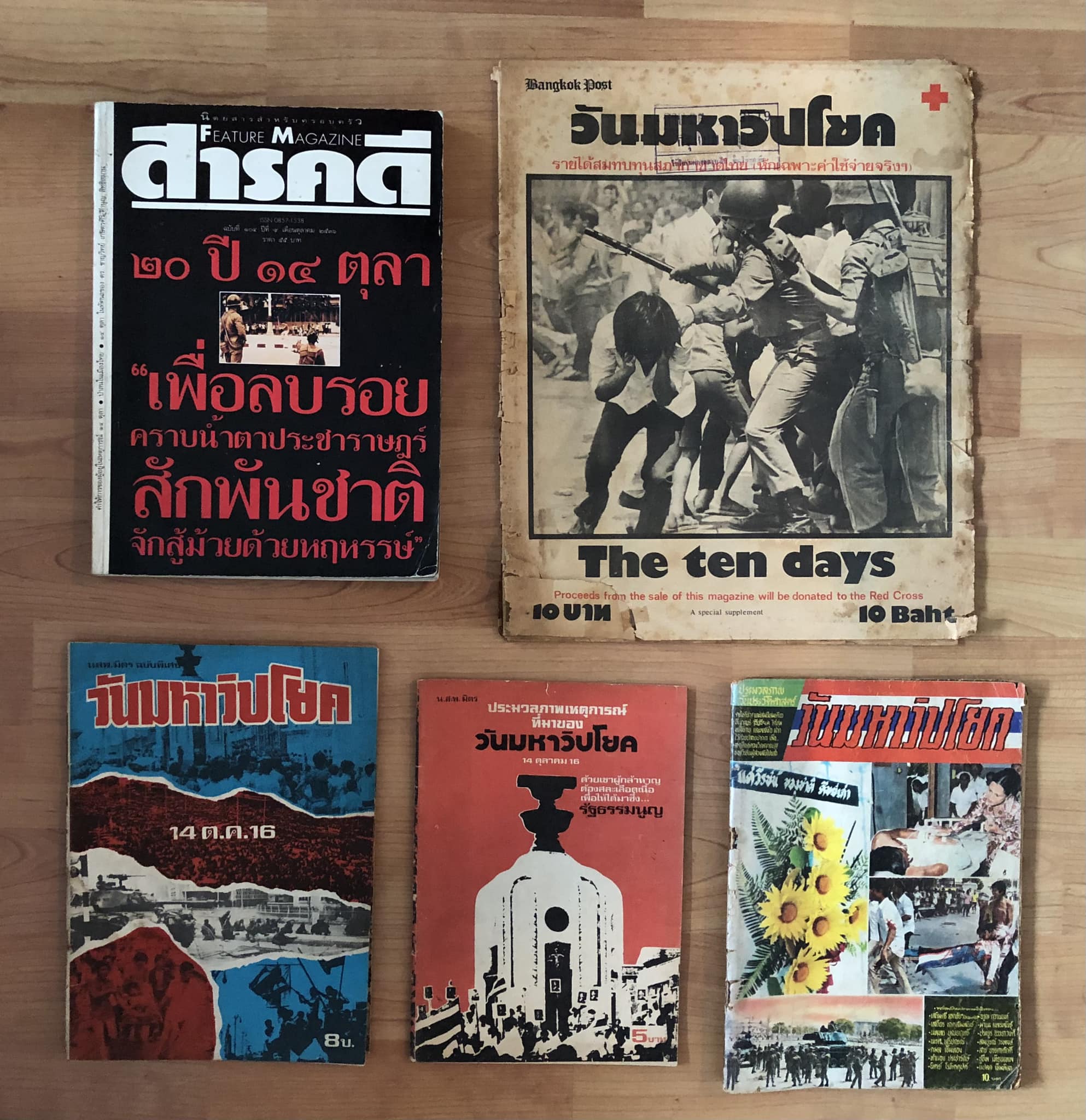

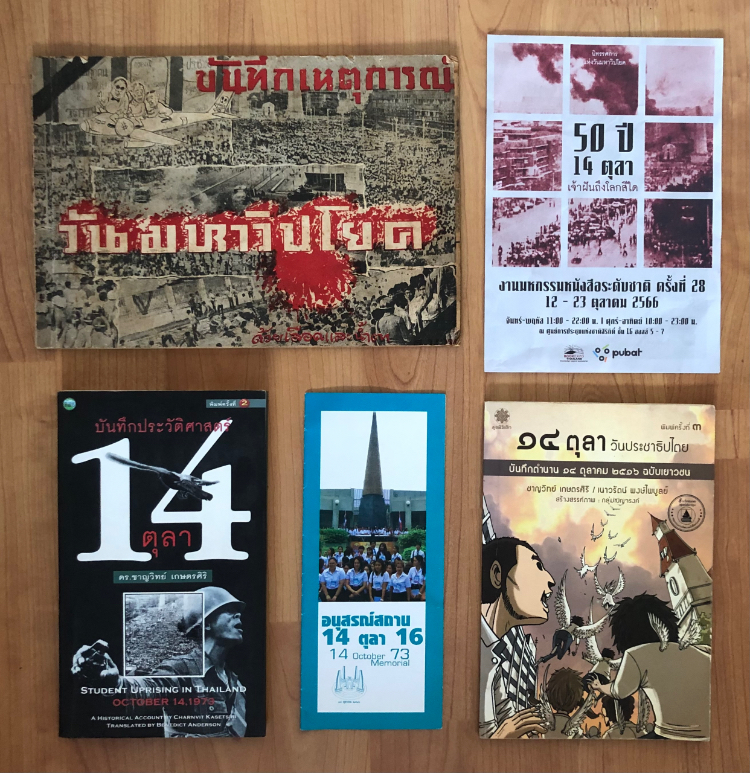

วัน (ไม่) สำคัญ, at Hope Space in Bangkok, is a series of activities commemorating significant political events that took place over the years in the month of October. The title, which translates as ‘the (not) important days’, is deeply ironic, as some of the most notorious dates in modern Thai history — not least, 14th October 1973 and 6th October 1976 — are related to October.

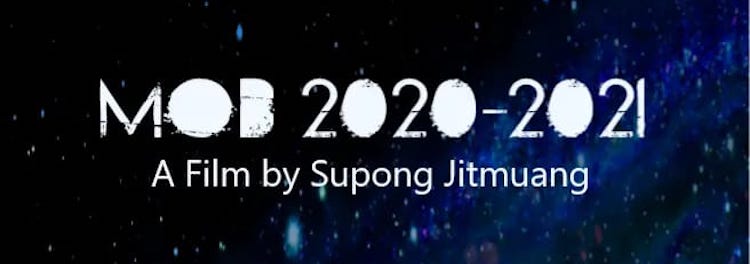

วัน (ไม่) สำคัญ runs from 16th to 31st October. Tomorrow, there will be screenings of two documentaries — Patporn Phoothong and Teerawat Rujenatham’s The Two Brothers (สองพี่น้อง), and Vichart Somkaew’s When My Father Was a Communist (เมื่อพ่อผมเป็นคอมมิวนิสต์) — followed by a Q&A with Vichart titled ความทรงจำสีแดง (‘red memories’).

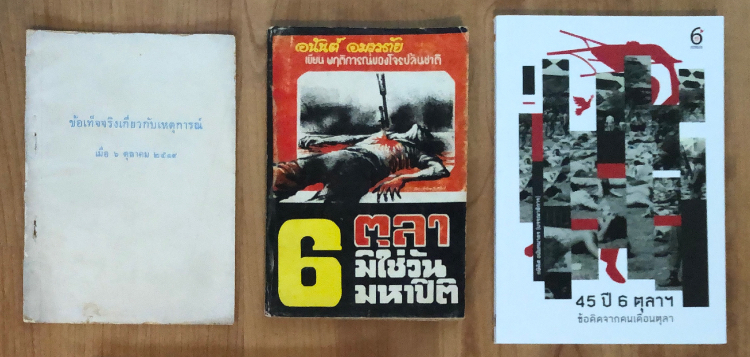

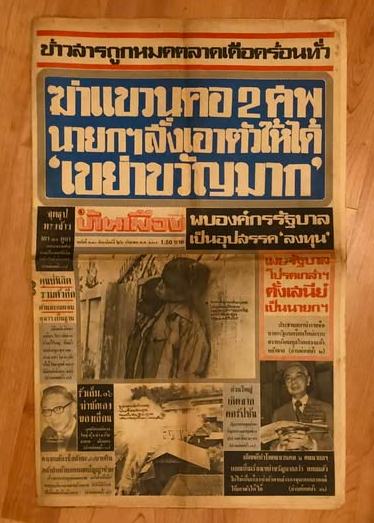

The short film The Two Brothers features interviews with relatives of two young men who were hanged by police for campaigning against the return of former dictator Thanom Kittikachorn from exile. It has previously been screened at Thammasat University in 2025, 2020, and 2017. It was last shown at Hope Space on 2nd October 2024.

The short film The Two Brothers features interviews with relatives of two young men who were hanged by police for campaigning against the return of former dictator Thanom Kittikachorn from exile. It has previously been screened at Thammasat University in 2025, 2020, and 2017. It was last shown at Hope Space on 2nd October 2024.

For When My Father Was a Communist, Vichart interviewed his father and other former members of the Communist Party of Thailand. The film has been screened around the country, including at Phimailongweek (พิมายฬองวีค) in Korat, and at the Chard Festival (ฉาด เฟสติวัล) in Phatthalung. It was last shown at Hope Space on 16th August.