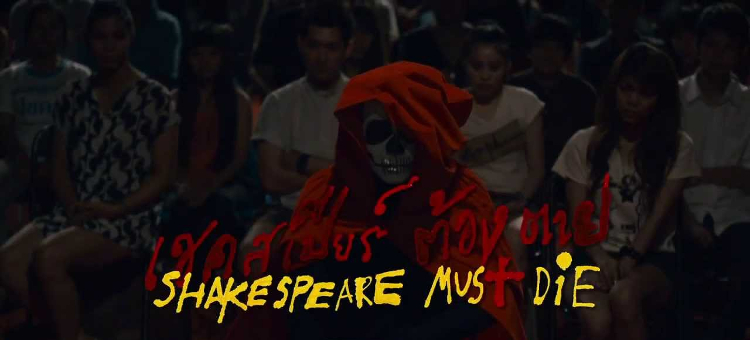

Ing K.’s Shakespeare Must Die (เชคสเปียร์ต้องตาย) will finally be released in Thai cinemas on 20th June, after more than a decade in legal limbo. The film was banned by the Ministry of Culture in 2012, and the ban was upheld by the Administrative Court in 2017. Ing’s battle with the censors, documented in her film Censor Must Die (เซ็นเซอร์ต้องตาย), went all the way to the Supreme Court, which lifted the ban in February following the liberalised censorship policy announced by the National Soft Power Strategy Committee at the start of this year.

Shakespeare Must Die is a Thai adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, with Pisarn Pattanapeeradej in the lead role. The play is presented in two parallel versions: a production in period costume, and a contemporary political interpretation. The period version is faithful to Shakespeare’s original, though it also breaks the fourth wall, with cutaways to the audience and an interval outside the theatre (featuring a cameo by the director).

In the contemporary sequences, Macbeth is reimagined as Mekhdeth, a prime minister facing a crisis. Street protesters shout “ok pbai!” (‘get out!’), and the protests are infiltrated by assassins listed in the credits as ‘men in black’. Ing has downplayed any direct link to Thai politics, though “Thaksin ok pbai!” was the People’s Alliance for Democracy’s rallying cry against Thaksin Shinawatra, and ‘men in black’ were blamed for instigating violence in 2010. Another satirical line in the script — “Dear Leader brings happy-ocracy!” — predicts Prayut Chan-o-cha’s propaganda song Returning Happiness to the Thai Kingdom (คืนความสุขให้ประเทศไทย).

The parallels between Mekhdeth and Thaksin highlight the politically-motivated nature of the ban imposed on the film. Ironically, the project was initially funded by the Ministry of Culture, during Abhisit Vejjajiva’s premiership: it received a grant from the ไทยเข้มแข็ง (‘strong Thailand’) stimulus package. The Abhisit government was only too happy to greenlight a script criticising Thaksin, though by the time the film was finished, Thaksin’s sister Yingluck was in power, and her administration was somewhat less disposed to this anti-Thaksin satire, hence the ban.

Although the film was made twelve years ago, its message is arguably more timely than ever, as Thaksin’s influence over Thai politics continues. He returned to Thailand last year, and his Pheu Thai Party is now leading a coalition with the political wing of the military junta.

The film’s climax, a recreation of the 6th October 1976 massacre, is its most controversial sequence. A photograph by Neal Ulevich, taken during the massacre, shows a vigilante preparing to hit a corpse with a chair, and Shakespeare Must Die restages the incident. A hanging body (symbolising Shakespeare himself) is repeatedly hit with a chair, though rather than dwelling on the violence, Ing cuts to reaction shots of the crowd, which (as in 1976) resembles a baying mob.

Ing was interviewed in Thai Cinema Uncensored, and the book details the full story behind the ban. Ing doesn’t mince her words in the interview, describing the censors as “a bunch of trembling morons with the power of life and death over our films.” Thai Cinema Uncensored also includes an insider’s account from a member of the appeals committee, who said he was obliged by his department head to vote against releasing the film: “I had to vote no, because it was an instruction from my director. But if I could have voted freely, I would have voted yes.”

Ing’s film My Teacher Eats Biscuits (คนกราบหมา) was also subject to a long-lasting ban, which was overturned last year. Shakespeare Must Die will be screened at Cinema Oasis, where My Teacher Eats Biscuits and Censor Must Die were both shown last month. There will also be an exhibition of costumes and props from Shakespeare Must Die and My Teacher Eats Biscuits — How to Make a Cheap Movie Look Good (ทำอย่างไรให้ / หนังทุนต่ำ / ดูดี?) — at Galerie Oasis from 20th June until 18th August.

Shakespeare Must Die is a Thai adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, with Pisarn Pattanapeeradej in the lead role. The play is presented in two parallel versions: a production in period costume, and a contemporary political interpretation. The period version is faithful to Shakespeare’s original, though it also breaks the fourth wall, with cutaways to the audience and an interval outside the theatre (featuring a cameo by the director).

In the contemporary sequences, Macbeth is reimagined as Mekhdeth, a prime minister facing a crisis. Street protesters shout “ok pbai!” (‘get out!’), and the protests are infiltrated by assassins listed in the credits as ‘men in black’. Ing has downplayed any direct link to Thai politics, though “Thaksin ok pbai!” was the People’s Alliance for Democracy’s rallying cry against Thaksin Shinawatra, and ‘men in black’ were blamed for instigating violence in 2010. Another satirical line in the script — “Dear Leader brings happy-ocracy!” — predicts Prayut Chan-o-cha’s propaganda song Returning Happiness to the Thai Kingdom (คืนความสุขให้ประเทศไทย).

The parallels between Mekhdeth and Thaksin highlight the politically-motivated nature of the ban imposed on the film. Ironically, the project was initially funded by the Ministry of Culture, during Abhisit Vejjajiva’s premiership: it received a grant from the ไทยเข้มแข็ง (‘strong Thailand’) stimulus package. The Abhisit government was only too happy to greenlight a script criticising Thaksin, though by the time the film was finished, Thaksin’s sister Yingluck was in power, and her administration was somewhat less disposed to this anti-Thaksin satire, hence the ban.

Although the film was made twelve years ago, its message is arguably more timely than ever, as Thaksin’s influence over Thai politics continues. He returned to Thailand last year, and his Pheu Thai Party is now leading a coalition with the political wing of the military junta.

The film’s climax, a recreation of the 6th October 1976 massacre, is its most controversial sequence. A photograph by Neal Ulevich, taken during the massacre, shows a vigilante preparing to hit a corpse with a chair, and Shakespeare Must Die restages the incident. A hanging body (symbolising Shakespeare himself) is repeatedly hit with a chair, though rather than dwelling on the violence, Ing cuts to reaction shots of the crowd, which (as in 1976) resembles a baying mob.

Ing was interviewed in Thai Cinema Uncensored, and the book details the full story behind the ban. Ing doesn’t mince her words in the interview, describing the censors as “a bunch of trembling morons with the power of life and death over our films.” Thai Cinema Uncensored also includes an insider’s account from a member of the appeals committee, who said he was obliged by his department head to vote against releasing the film: “I had to vote no, because it was an instruction from my director. But if I could have voted freely, I would have voted yes.”

Ing’s film My Teacher Eats Biscuits (คนกราบหมา) was also subject to a long-lasting ban, which was overturned last year. Shakespeare Must Die will be screened at Cinema Oasis, where My Teacher Eats Biscuits and Censor Must Die were both shown last month. There will also be an exhibition of costumes and props from Shakespeare Must Die and My Teacher Eats Biscuits — How to Make a Cheap Movie Look Good (ทำอย่างไรให้ / หนังทุนต่ำ / ดูดี?) — at Galerie Oasis from 20th June until 18th August.