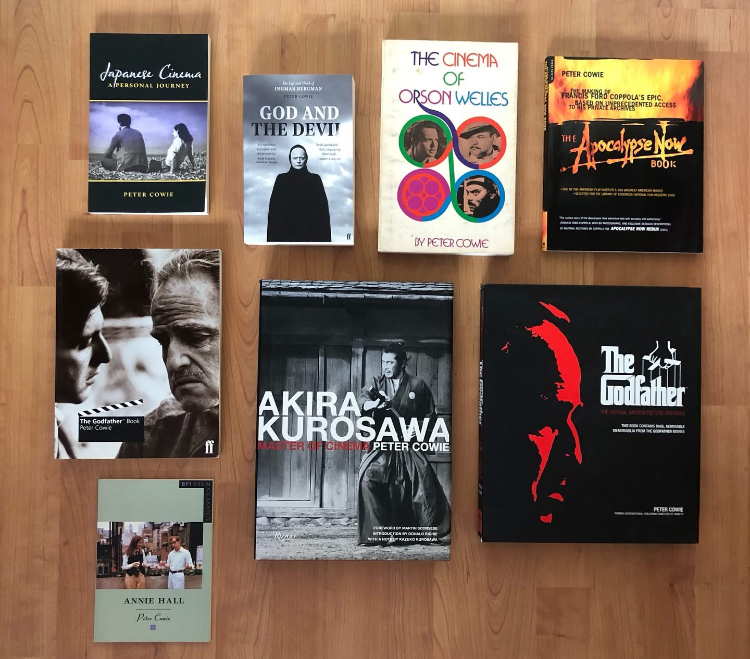

Peter Cowie’s Japanese Cinema: A Personal Journey profiles some of Japan’s greatest directors and features concise reviews of their key films. Cowie has previously written a more substantial book on Akira Kurosawa, which divided Kurosawa’s films into modern and historical narratives (the traditional Japanese distinction between gendai-geki and jidai-geki), though in Japanese Cinema he focuses almost entirely on Kurosawa’s samurai films.

The book is a short primer on the major figures in Japanese film, and includes chapters on Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hayao Miyazaki, and others. It’s dedicated to the late Donald Richie, who wrote influential studies of Kurosawa (The Films of Akira Kurosawa) and Japanese cinema history (A Hundred Years of Japanese Film). Cowie writes a chapter on the Japanese new wave, though David Desser’s book Eros Plus Massacre is a more comprehensive account.

The book is a short primer on the major figures in Japanese film, and includes chapters on Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hayao Miyazaki, and others. It’s dedicated to the late Donald Richie, who wrote influential studies of Kurosawa (The Films of Akira Kurosawa) and Japanese cinema history (A Hundred Years of Japanese Film). Cowie writes a chapter on the Japanese new wave, though David Desser’s book Eros Plus Massacre is a more comprehensive account.

Cowie has written and published dozens of books on cinema, from an early monograph on Orson Welles (A Ribbon of Dreams) to a recent biography of Ingmar Bergman (God and the Devil). His books on the making of The Godfather and Apocalypse Now are indispensable; his second Godfather book was published fifteen years after the first, and he also wrote a book on another 1970s classic, Annie Hall.