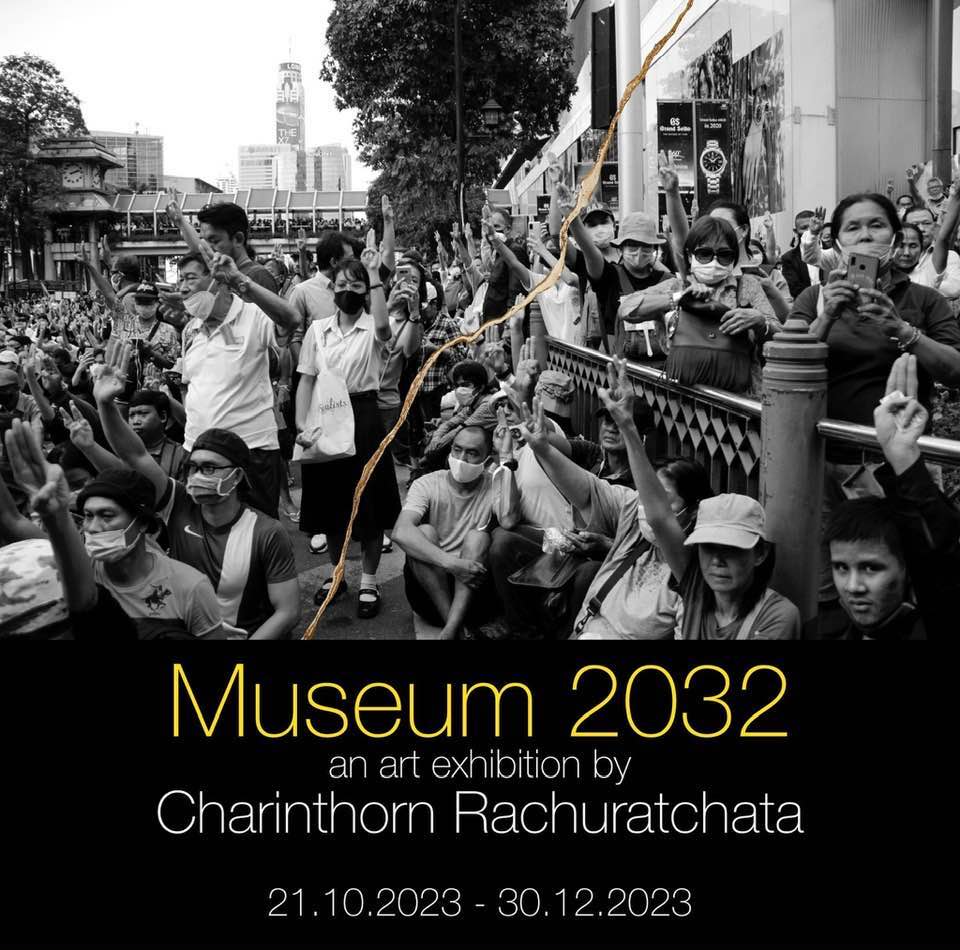

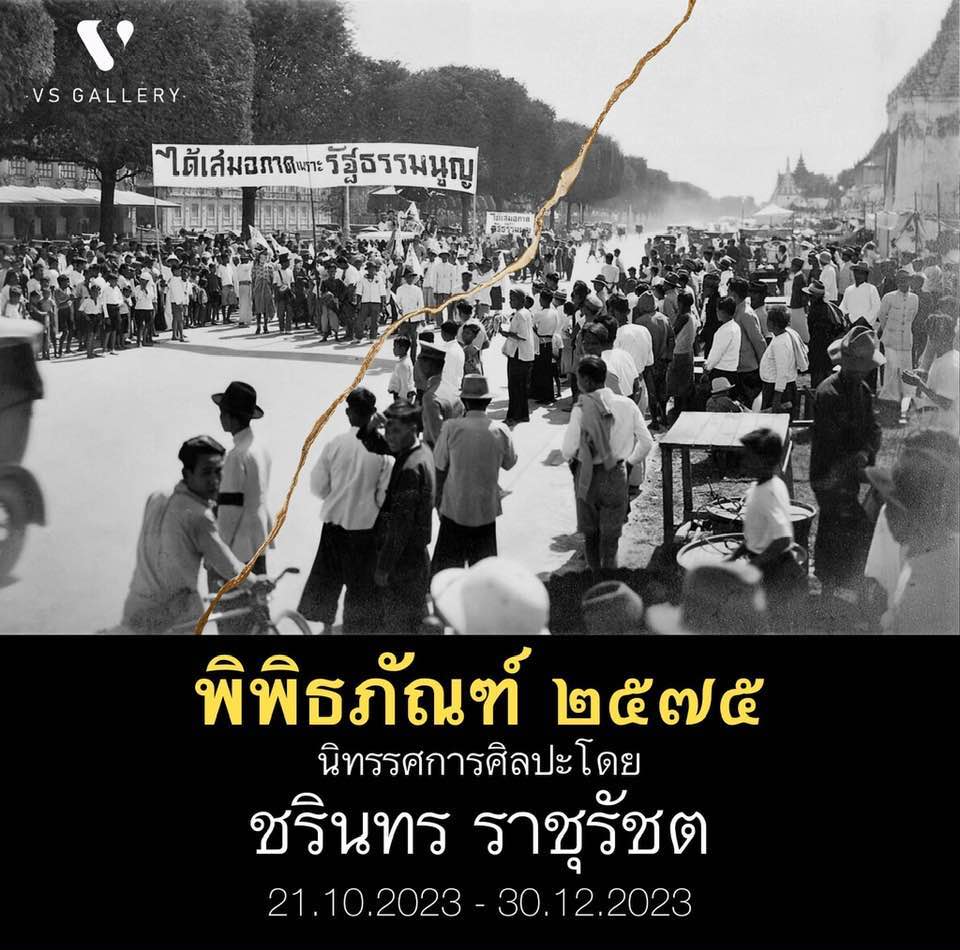

An exhibition of satirical memes and online political cartoons opens this week at All Rise (the offices of iLaw) in Bangkok. Memes of Dissent: Thai Social Media During the 2020–2021 Student Uprising (โซเชียลเน็ตเวิร์คในท่ามกลางการประท้วงของนักศึกษาไทยระหว่างปี 2020–2021) features anti-government GIFs and other digital artwork shared via social media in support of the student protest movement that began in 2020.

The exhibition was previously held at Artcade in Phayao, where it was on show for almost two months (from 3rd August to 1st October 2023), though it will only be open for three days in Bangkok, from 26th to 28th January. Organised by the University of Phayao’s School of Architecture and Fine Art in association with the Museum of Popular History, the Bangkok exhibition will also include memes created after last year’s election (when the winning party was sidelined and the military remained in government).

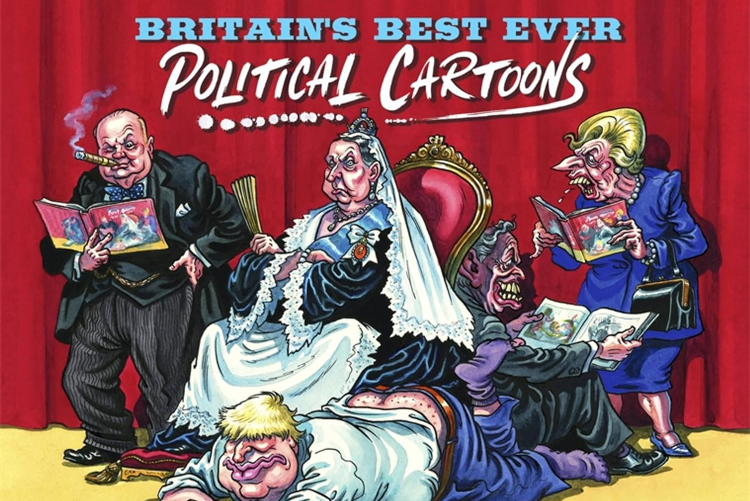

Copies of คนกลมคนเหลี่ยม Live in Memes of Dissent (‘round people and square people live in memes of dissent’) will be given away at the exhibition. The booklet—limited to fifty copies—reprints a dozen cartoons from the คนกลมคนเหลี่ยม (‘round people and square people’) Facebook page, in solidarity with the cartoonist, who is facing lèse-majesté charges in relation to four cartoons he posted on the page in 2022. (Another Facebook cartoonist, BackArt, has also been charged with lèse-majesté, in relation to two cartoons he posted in 2021.)

The exhibition was previously held at Artcade in Phayao, where it was on show for almost two months (from 3rd August to 1st October 2023), though it will only be open for three days in Bangkok, from 26th to 28th January. Organised by the University of Phayao’s School of Architecture and Fine Art in association with the Museum of Popular History, the Bangkok exhibition will also include memes created after last year’s election (when the winning party was sidelined and the military remained in government).

Copies of คนกลมคนเหลี่ยม Live in Memes of Dissent (‘round people and square people live in memes of dissent’) will be given away at the exhibition. The booklet—limited to fifty copies—reprints a dozen cartoons from the คนกลมคนเหลี่ยม (‘round people and square people’) Facebook page, in solidarity with the cartoonist, who is facing lèse-majesté charges in relation to four cartoons he posted on the page in 2022. (Another Facebook cartoonist, BackArt, has also been charged with lèse-majesté, in relation to two cartoons he posted in 2021.)