John A. Lent’s Asian Political Cartoons is a remarkable and comprehensive book, covering the history of political cartoons in no fewer than twenty countries. As the publisher claims, with justification, it is “not only the first such survey in English, but the most complete and detailed in any language.” Lent has interviewed more than 200 cartoonists—most notably, Zunar in Malaysia—and made multiple research trips to each of the countries he documents.

Histories of political cartoons traditionally focus on revolutionary France, Georgian Britain, and the Reconstruction era in the United States. Lent’s book, on the other hand, is a window into a previously inaccessible world of satirical art. He shows how cartoonists have challenged authoritarian regimes throughout Asia, and assesses the varying degrees of “freedom to cartoon” in the region (such as the repressive treatment of Mana Neyestani in Iran and Arifur Rahman in Bangladesh).

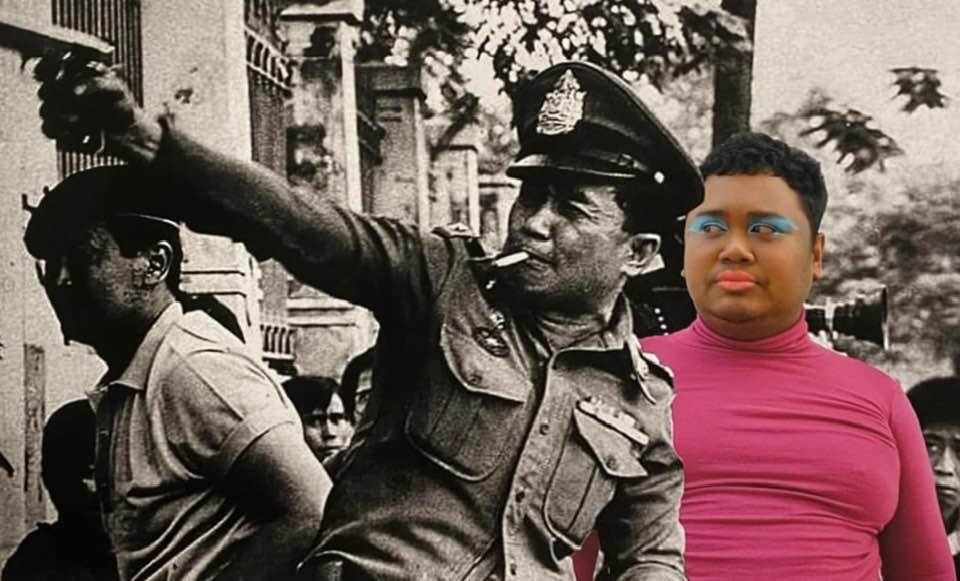

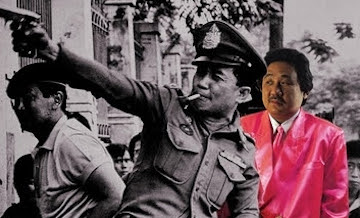

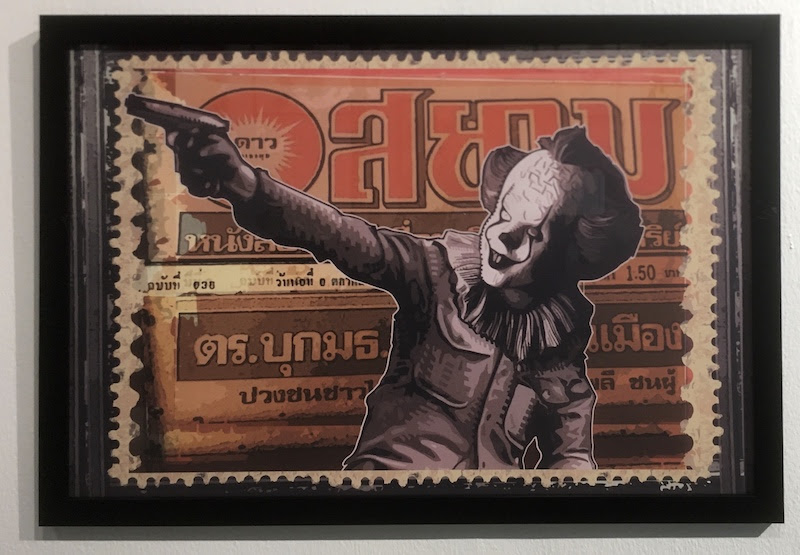

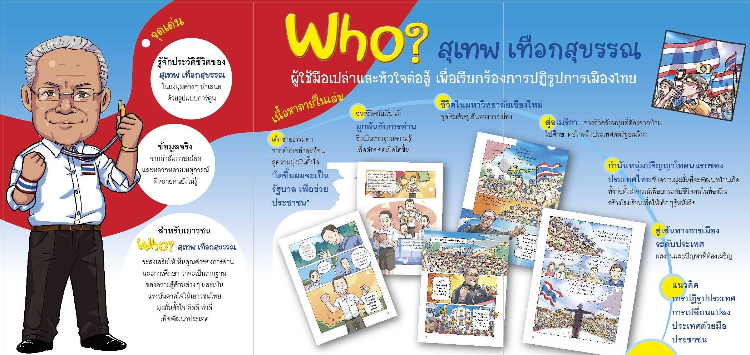

For his chapter on Thailand, Lent interviewed Chai Rachawat and Arun Watcharasawad, veteran cartoonists who have covered Thai politics since the 1970s for Thai Rath (ไทยรัฐ) and Matichon (มติชน), respectively. He discussed the Thaksin Shinawatra era with Buncha and Kamin from Manager (ผู้จัดการรายวัน), and he describes the enforced ‘attitude adjustment’ of another Thai Rath cartoonist, Sia, under Prayut Chan-o-cha’s military rule. He also covers the rise of anonymous online satirists such as Khai Maew. (Sia wasn’t interviewed for the book, though he spoke to Dateline Bangkok last year.)

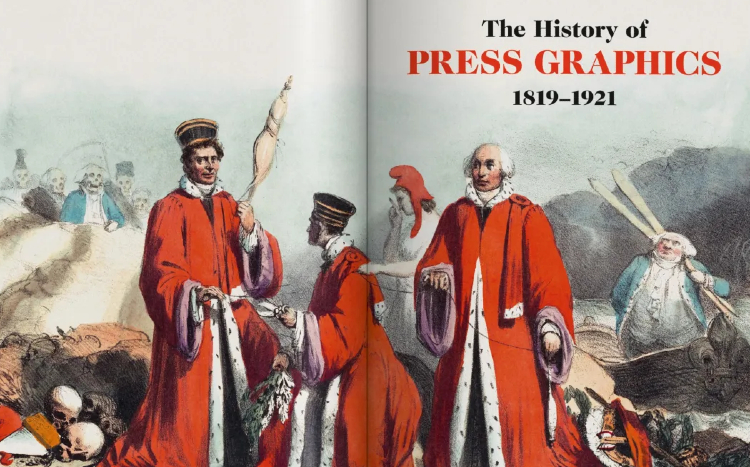

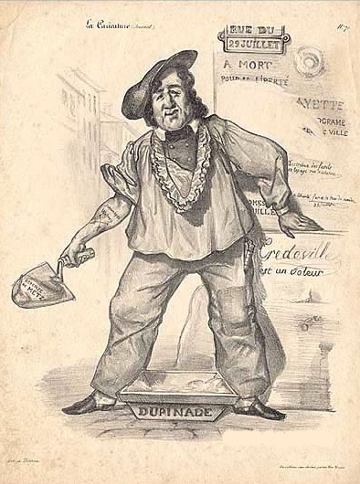

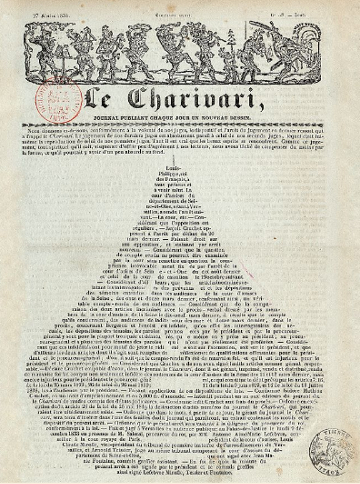

The scope of Asian Political Cartoons is unprecedented, though Cherian George’s Red Lines also examines political cartooning from an international perspective. Victor S. Navasky’s The Art of Controversy covers European and American political cartoons, and Alexander Roob reproduces early newspaper cartoons in The History of Press Graphics 1819–1921.

Histories of political cartoons traditionally focus on revolutionary France, Georgian Britain, and the Reconstruction era in the United States. Lent’s book, on the other hand, is a window into a previously inaccessible world of satirical art. He shows how cartoonists have challenged authoritarian regimes throughout Asia, and assesses the varying degrees of “freedom to cartoon” in the region (such as the repressive treatment of Mana Neyestani in Iran and Arifur Rahman in Bangladesh).

For his chapter on Thailand, Lent interviewed Chai Rachawat and Arun Watcharasawad, veteran cartoonists who have covered Thai politics since the 1970s for Thai Rath (ไทยรัฐ) and Matichon (มติชน), respectively. He discussed the Thaksin Shinawatra era with Buncha and Kamin from Manager (ผู้จัดการรายวัน), and he describes the enforced ‘attitude adjustment’ of another Thai Rath cartoonist, Sia, under Prayut Chan-o-cha’s military rule. He also covers the rise of anonymous online satirists such as Khai Maew. (Sia wasn’t interviewed for the book, though he spoke to Dateline Bangkok last year.)

The scope of Asian Political Cartoons is unprecedented, though Cherian George’s Red Lines also examines political cartooning from an international perspective. Victor S. Navasky’s The Art of Controversy covers European and American political cartoons, and Alexander Roob reproduces early newspaper cartoons in The History of Press Graphics 1819–1921.