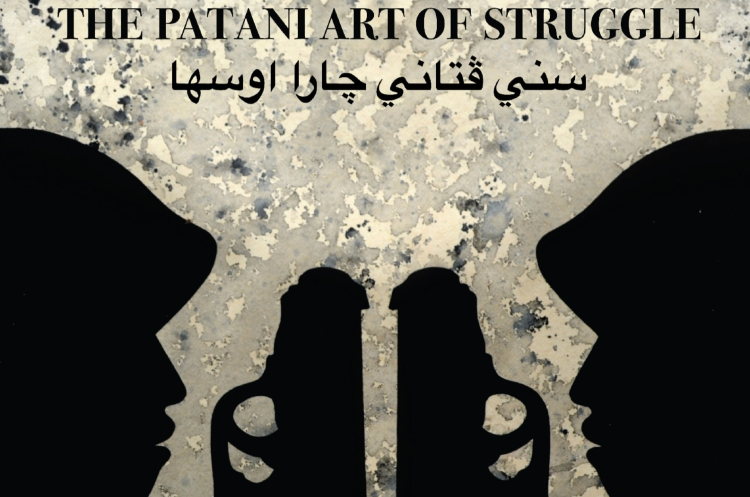

Jehabdulloh Jehsorhoh has led a burgeoning of contemporary art in Pattani and the other provinces near Thailand’s southern border, and The Patani Art of Struggle (ศิลปะปาตานี วิถีแห่งการดิ้นรน), a monograph on Jehabdulloh’s work, was published last year. (‘Patani’ refers to a formerly independent Malay Muslim sultanate that is now part of Thailand. Today, therefore, ‘Patani’ is a political term with separatist connotations.)

Jehabdulloh first came to prominence with Violence in Tak-Bai (ความรุนแรงที่ตากใบ): wooden grave markers arranged in a circle, commemorating the protesters who died in the 2004 Tak Bai massacre. The book reproduces a watercolour painting of the concept, and three versions of the installation in situ. It was first installed, just a few days after the massacre, at the Prince of Songkla University campus in Pattani, and the grave markers were accompanied by rifles wrapped in white cloth. In 2017, it was recreated at Patani Art Space and exhibited on a plinth containing Pattani soil at the Patani Semasa (ปาตานี ร่วมสมัย) exhibition. (The exhibition catalogue gives it a milder alternative title, Remember at Tak-Bai.)

Since 2013, Jehabdulloh has incorporated images of weapons such as guns and hand grenades into his paintings, a reminder of the continuing conflict between the Thai military and separatist insurgents. The book highlights the financial and human cost of the military operation: “The Thai government has spent ฿206,094 million to solve and alleviate the conflicts in Southern Thailand over the past ten years... Is fighting violence with violence an effective solution?” Yuthlert Sippapak’s film Fatherland (ปิตุภูมิ) poses the same question, as he explained in an interview for Thai Cinema Uncensored: “‘เหตุการณ์สงบงบไม่มา’ — ‘if no war, no money’. Money is power. And the person who created the war is the military.”

The Patani Art of Struggle, housed in a die-cut slipcase, was edited by Apichaya O-in and Ekkarin Tuansiri. Its Malay title is سني ڤتاني چاراو او سها.

Jehabdulloh first came to prominence with Violence in Tak-Bai (ความรุนแรงที่ตากใบ): wooden grave markers arranged in a circle, commemorating the protesters who died in the 2004 Tak Bai massacre. The book reproduces a watercolour painting of the concept, and three versions of the installation in situ. It was first installed, just a few days after the massacre, at the Prince of Songkla University campus in Pattani, and the grave markers were accompanied by rifles wrapped in white cloth. In 2017, it was recreated at Patani Art Space and exhibited on a plinth containing Pattani soil at the Patani Semasa (ปาตานี ร่วมสมัย) exhibition. (The exhibition catalogue gives it a milder alternative title, Remember at Tak-Bai.)

Since 2013, Jehabdulloh has incorporated images of weapons such as guns and hand grenades into his paintings, a reminder of the continuing conflict between the Thai military and separatist insurgents. The book highlights the financial and human cost of the military operation: “The Thai government has spent ฿206,094 million to solve and alleviate the conflicts in Southern Thailand over the past ten years... Is fighting violence with violence an effective solution?” Yuthlert Sippapak’s film Fatherland (ปิตุภูมิ) poses the same question, as he explained in an interview for Thai Cinema Uncensored: “‘เหตุการณ์สงบงบไม่มา’ — ‘if no war, no money’. Money is power. And the person who created the war is the military.”

The Patani Art of Struggle, housed in a die-cut slipcase, was edited by Apichaya O-in and Ekkarin Tuansiri. Its Malay title is سني ڤتاني چاراو او سها.