Thailand’s politics had been polarised for almost a decade by 2013, between the yellow-shirt and red-shirt movements. Yingluck Shinawatra managed the impossible, by bringing both sides together in a common cause — though they were united against one of her Pheu Thai government’s key policies, a blanket amnesty for those accused of political crimes. The proposed amnesty would have given immunity to Abhisit Vejjajiva over his role in the deadly crackdown on red-shirt protesters in 2010, though the bill was widely perceived as a cover to exonerate Yingluck’s brother Thaksin of his corruption charges.

The amnesty bill was approved by parliament on 1st November 2013, thanks to Pheu Thai’s majority in the House of Representatives, though the vote was held at 4am, in a misguided attempt to pass it without drawing attention to the legislation. Protests against the amnesty took place in Bangkok, and the bill was unanimously rejected by the Senate, on 11th November 2013.

The amnesty bill was approved by parliament on 1st November 2013, thanks to Pheu Thai’s majority in the House of Representatives, though the vote was held at 4am, in a misguided attempt to pass it without drawing attention to the legislation. Protests against the amnesty took place in Bangkok, and the bill was unanimously rejected by the Senate, on 11th November 2013.

At the same time, on 20th November 2013, the Constitutional Court rejected an attempt by Pheu Thai to amend the constitution and return to an entirely elected Senate. (Under the previous 1997 constitution, the Senate had become fully democratic for the first time, though the subsequent constitution drafted after the 2006 coup created a half-elected and half-appointed Senate.)

In a highly unusual and provocative step, Pheu Thai publicly rejected the court’s verdict, and even called for the impeachment of the five judges who voted against the government. Yingluck ultimately withdrew the proposed amendment, and dropped all plans for an amnesty, though these concessions emboldened the anti-government protesters to increase their campaign, calling for the eradication of what they called the Thaksin regime.

In a highly unusual and provocative step, Pheu Thai publicly rejected the court’s verdict, and even called for the impeachment of the five judges who voted against the government. Yingluck ultimately withdrew the proposed amendment, and dropped all plans for an amnesty, though these concessions emboldened the anti-government protesters to increase their campaign, calling for the eradication of what they called the Thaksin regime.

People’s Democratic Reform Committee

Mass demonstrations began on the weekend of 23rd and 24th November 2013, when around 100,000 protesters gathered at Democracy Monument. Suthep Thaugsuban, a senior figure in the opposition Democrat Party, resigned as an MP to lead a new protest group, the People’s Democratic Reform Committee. The PDRC briefly occupied the offices of several government ministries on 25th November 2013.

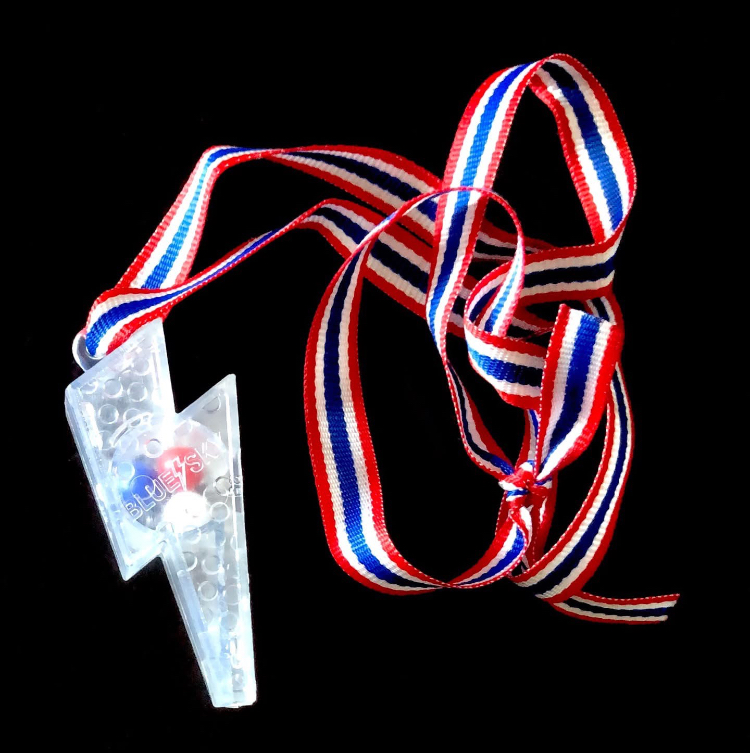

PDRC protesters carried whistles instead of the hand-clappers used in previous demonstrations, though in other respects they followed the yellow-shirt playbook. Their street protests caused maximum disruption in Bangkok, provoking a political crisis, and creating the conditions for a military coup.

In 2010, when Suthep was in government and the red-shirt rallies were at their height, Suthep said: “if they violate the laws, such as blocking roads and intruding into government offices, we will have to disperse the protesters.” But, three years later, he was using precisely the tactics that he had previously condemned.

PDRC protesters carried whistles instead of the hand-clappers used in previous demonstrations, though in other respects they followed the yellow-shirt playbook. Their street protests caused maximum disruption in Bangkok, provoking a political crisis, and creating the conditions for a military coup.

In 2010, when Suthep was in government and the red-shirt rallies were at their height, Suthep said: “if they violate the laws, such as blocking roads and intruding into government offices, we will have to disperse the protesters.” But, three years later, he was using precisely the tactics that he had previously condemned.

On 9th December 2013, all Democrat Party MPs resigned from parliament and the PDRC led around 160,000 people in a march to Government House. Yingluck dissolved parliament and called a general election for 2nd February 2014, though the Democrats announced that they would boycott the vote.

Registration for the election took place at the Bangkok Youth Centre stadium, and the PDRC began one of its biggest rallies there on 22nd December 2013. After four days, on Boxing Day, the police used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the protesters, and a police officer was killed.

Suthep escalated his protests, announcing a ‘Shutdown Bangkok’ campaign that began on 13th January 2014, designed to cause gridlock in the capital city and sabotage the election. Yingluck declared a state of emergency on 22nd January 2014, and four days later the PDRC blocked access to polling stations to prevent early voting in the election.

Registration for the election took place at the Bangkok Youth Centre stadium, and the PDRC began one of its biggest rallies there on 22nd December 2013. After four days, on Boxing Day, the police used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the protesters, and a police officer was killed.

Suthep escalated his protests, announcing a ‘Shutdown Bangkok’ campaign that began on 13th January 2014, designed to cause gridlock in the capital city and sabotage the election. Yingluck declared a state of emergency on 22nd January 2014, and four days later the PDRC blocked access to polling stations to prevent early voting in the election.

On election day, 11% of polling stations were closed due to PDRC protests, and voting was cancelled in nine provinces. On the eve of the election, a lone gunman shot four pro-democracy demonstrators at Lak Si in Bangkok. (His M16 rifle was concealed in a Kolk popcorn bag, which became a tasteless fashion accessory among some PDRC members.)

After months of disruption, riot police began attempting to reclaim some of the blockaded buildings and roads in Bangkok. On 18th February 2014, four protesters and a police officer were killed at Phan Fah when protesters attacked the police with grenades and gunfire, and the police responded with live ammunition. Suthep finally ended his shutdown on 3rd March 2014.

After months of disruption, riot police began attempting to reclaim some of the blockaded buildings and roads in Bangkok. On 18th February 2014, four protesters and a police officer were killed at Phan Fah when protesters attacked the police with grenades and gunfire, and the police responded with live ammunition. Suthep finally ended his shutdown on 3rd March 2014.

The 2014 Coup

On 20th March 2014, army chief Prayut Chan-o-cha announced that the military had taken over control of national security. In a televised broadcast, he sought to reassure the public: “We urge people not to panic. Please carry on your daily activities as usual. The invocation of martial law is not a coup d’etat”

Two days later, Prayut led the National Council for Peace and Order in a military coup against the Pheu Thai government. He was appointed prime minister on 21st August 2014, a role he held for nine years.

Thai Political Milestones:

Two days later, Prayut led the National Council for Peace and Order in a military coup against the Pheu Thai government. He was appointed prime minister on 21st August 2014, a role he held for nine years.

Thai Political Milestones:

- no. 1: ‘Black May’

- no. 2: 14th October 1973

- no. 3: 6th October 1976

- no. 4: Yellow-shirts v. Red-shirts

- no. 5: ‘Three-finger’ Protests