In anticipation of the Bangkok Critics Assembly Awards, honouring the best Thai films released last year, the shortlisted feature films will be shown at Century Sukhumvit between 13th and 17th September, followed by Q&A sessions with their respective directors. The nominated films include Taklee Genesis (ตาคลี เจเนซิส) screening on 13th September, Shakespeare Must Die (เชคสเปียร์ต้องตาย) on 14th September, and Breaking the Cycle (อำนาจ ศรัทธา อนาคต) on 16th September.

Taklee Genesis

Chookiat Sakveerakul’s Taklee Genesis features time travel, dinosaurs, kaiju monsters, zombies, cavemen, the Cold War, a dystopian future, and the 6th October 1976 massacre at Thammasat University, all woven together into an ambitious sci-fi epic. (It was shown earlier this year at the Thai Film Archive.)

In a prologue that takes place in May 1992 (an unspoken reference to ‘Black May’), a young girl witnesses “dead bodies falling from the sky.” These are students who died during the Thammasat tragedy, their bodies teleported by the Taklee Genesis device, a time machine that can create alternate realities. As one character says: “Taklee Genesis was used to cover up a massacre.”

When the girl, Stella, grows up, she learns that her father was a CIA agent involved in the development of the Taklee Genesis. One of the project’s test subjects, Lawan, was transformed into a forest-dwelling spirit, like the monkey ghost in Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (ลุงบุญมีระลึกชาติ), another supernatural personification of the legacy of the Cold War.

Stella and her friend Kong use the Taklee Genesis to travel back in time to Thammasat on 6th October 1976, after Kong discovers that he is one of the massacre victims who fell from the sky. Chookiat recreates the violence of that day, showing Red Gaur militiamen gunning down students. A young boy stands alone on a balcony laughing at the carnage, in a reference to a smiling onlooker in a photograph by Neal Ulevich. (The artist Khai Maew created a model of the child, which he called Happy Boy.)

Thanks to the Taklee Genesis, Kong has the chance to fight back against the vigilantes who have stormed the campus. This fantasy scenario, in which a Thammasat victim is given the agency to tackle his potential killers, is similar to the alternate history narrative in Preecha Raksorn’s comic strip Once Upon a Time at..., in which the victim in Ulevich’s photograph escapes from his assailant.

Discussion of the Thammasat massacre was suppressed for years, not by the fictional Taklee Genesis device, but instead by successive military governments. Today, it’s primarily through photographs of the event, particularly the famous image by Ulevich, that the incident is remembered. In one of the film’s most powerful moments, Kong takes a roll of film from the camera of his Thammasat classmate and gives it to Stella, telling her: “Make sure we’re not forgotten.”

The Thammasat massacre is a notorious incident in Thailand’s modern history, though it has rarely been represented on screen. The 6th October scenes in Taklee Genesis are almost unprecedented: the only previous attempt to dramatise the brutality of the event was in the horror film Haunted Universities (มหาลัยสยองขวัญ), which was cut by the Thai film censors.

In a prologue that takes place in May 1992 (an unspoken reference to ‘Black May’), a young girl witnesses “dead bodies falling from the sky.” These are students who died during the Thammasat tragedy, their bodies teleported by the Taklee Genesis device, a time machine that can create alternate realities. As one character says: “Taklee Genesis was used to cover up a massacre.”

When the girl, Stella, grows up, she learns that her father was a CIA agent involved in the development of the Taklee Genesis. One of the project’s test subjects, Lawan, was transformed into a forest-dwelling spirit, like the monkey ghost in Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (ลุงบุญมีระลึกชาติ), another supernatural personification of the legacy of the Cold War.

Stella and her friend Kong use the Taklee Genesis to travel back in time to Thammasat on 6th October 1976, after Kong discovers that he is one of the massacre victims who fell from the sky. Chookiat recreates the violence of that day, showing Red Gaur militiamen gunning down students. A young boy stands alone on a balcony laughing at the carnage, in a reference to a smiling onlooker in a photograph by Neal Ulevich. (The artist Khai Maew created a model of the child, which he called Happy Boy.)

Thanks to the Taklee Genesis, Kong has the chance to fight back against the vigilantes who have stormed the campus. This fantasy scenario, in which a Thammasat victim is given the agency to tackle his potential killers, is similar to the alternate history narrative in Preecha Raksorn’s comic strip Once Upon a Time at..., in which the victim in Ulevich’s photograph escapes from his assailant.

Discussion of the Thammasat massacre was suppressed for years, not by the fictional Taklee Genesis device, but instead by successive military governments. Today, it’s primarily through photographs of the event, particularly the famous image by Ulevich, that the incident is remembered. In one of the film’s most powerful moments, Kong takes a roll of film from the camera of his Thammasat classmate and gives it to Stella, telling her: “Make sure we’re not forgotten.”

The Thammasat massacre is a notorious incident in Thailand’s modern history, though it has rarely been represented on screen. The 6th October scenes in Taklee Genesis are almost unprecedented: the only previous attempt to dramatise the brutality of the event was in the horror film Haunted Universities (มหาลัยสยองขวัญ), which was cut by the Thai film censors.

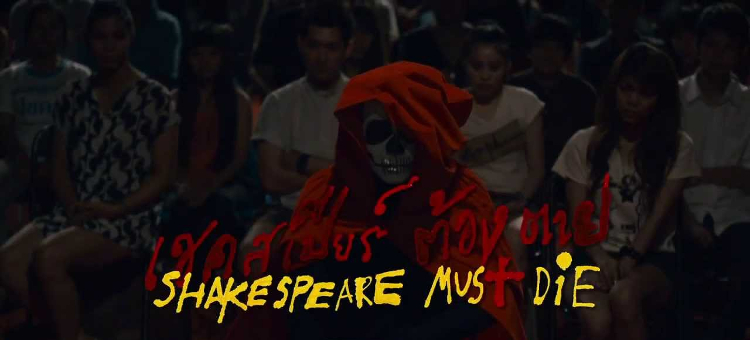

Shakespeare Must Die

Shakespeare Must Die, directed by Ing K., is a Thai adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, with Pisarn Pattanapeeradej in the lead role. The play is presented in two parallel versions: a production in period costume, and a contemporary political interpretation. The period version is faithful to Shakespeare’s original, though it also breaks the fourth wall, with cutaways to the audience and an interval outside the theatre (featuring a cameo by the director).

In the contemporary sequences, Macbeth is reimagined as Mekhdeth, a prime minister facing a crisis. Street protesters shout “ok pbai!” (‘get out!’), and the protests are infiltrated by assassins listed in the credits as ‘men in black’. Ing has downplayed any direct link to Thai politics, though “Thaksin ok pbai!” was the People’s Alliance for Democracy’s rallying cry against Thaksin Shinawatra, and ‘men in black’ were blamed for instigating violence in 2010. Another satirical line in the script — “Dear Leader brings happy-ocracy!” — predicts Prayut Chan-o-cha’s propaganda song Returning Happiness to the Thai Kingdom (คืนความสุขให้ประเทศไทย).

The parallels between Mekhdeth and Thaksin highlight the politically-motivated nature of the ban imposed on the film in 2012. Ironically, the project was initially funded by the Ministry of Culture, during Abhisit Vejjajiva’s premiership: it received a grant from the ไทยเข้มแข็ง (‘strong Thailand’) stimulus package. The Abhisit government was only too happy to greenlight a script criticising Thaksin, though by the time the film was finished, Thaksin’s sister Yingluck was in power, and her administration was somewhat less disposed to this anti-Thaksin satire, hence the ban.

The film’s climax, a recreation of the Thammasat massacre, is its most controversial sequence. A photograph by Neal Ulevich, taken during the massacre, shows a vigilante preparing to hit a corpse with a chair, and Shakespeare Must Die restages the incident. A hanging body (symbolising Shakespeare himself) is repeatedly hit with a chair, though rather than dwelling on the violence, Ing cuts to reaction shots of the crowd, which (as in 1976) resembles a baying mob.

When I interviewed her for Thai Cinema Uncensored, Ing didn’t mince her words, describing the censors as “a bunch of trembling morons with the power of life and death over our films.” Thai Cinema Uncensored also includes an insider’s account from a member of the appeals committee, who said he was obliged by his department head to vote against releasing the film: “I had to vote no, because it was an instruction from my director. But if I could have voted freely, I would have voted yes.”

The ban on Shakespeare Must Die was finally lifted by the Supreme Court last year, and its theatrical release came a few months later. It has since been shown at Burapha University and Chiang Mai University, and its most recent screening was at the Phimailongweek (พิมายฬองวีค) experimental arts festival in Korat.

In the contemporary sequences, Macbeth is reimagined as Mekhdeth, a prime minister facing a crisis. Street protesters shout “ok pbai!” (‘get out!’), and the protests are infiltrated by assassins listed in the credits as ‘men in black’. Ing has downplayed any direct link to Thai politics, though “Thaksin ok pbai!” was the People’s Alliance for Democracy’s rallying cry against Thaksin Shinawatra, and ‘men in black’ were blamed for instigating violence in 2010. Another satirical line in the script — “Dear Leader brings happy-ocracy!” — predicts Prayut Chan-o-cha’s propaganda song Returning Happiness to the Thai Kingdom (คืนความสุขให้ประเทศไทย).

The parallels between Mekhdeth and Thaksin highlight the politically-motivated nature of the ban imposed on the film in 2012. Ironically, the project was initially funded by the Ministry of Culture, during Abhisit Vejjajiva’s premiership: it received a grant from the ไทยเข้มแข็ง (‘strong Thailand’) stimulus package. The Abhisit government was only too happy to greenlight a script criticising Thaksin, though by the time the film was finished, Thaksin’s sister Yingluck was in power, and her administration was somewhat less disposed to this anti-Thaksin satire, hence the ban.

The film’s climax, a recreation of the Thammasat massacre, is its most controversial sequence. A photograph by Neal Ulevich, taken during the massacre, shows a vigilante preparing to hit a corpse with a chair, and Shakespeare Must Die restages the incident. A hanging body (symbolising Shakespeare himself) is repeatedly hit with a chair, though rather than dwelling on the violence, Ing cuts to reaction shots of the crowd, which (as in 1976) resembles a baying mob.

When I interviewed her for Thai Cinema Uncensored, Ing didn’t mince her words, describing the censors as “a bunch of trembling morons with the power of life and death over our films.” Thai Cinema Uncensored also includes an insider’s account from a member of the appeals committee, who said he was obliged by his department head to vote against releasing the film: “I had to vote no, because it was an instruction from my director. But if I could have voted freely, I would have voted yes.”

The ban on Shakespeare Must Die was finally lifted by the Supreme Court last year, and its theatrical release came a few months later. It has since been shown at Burapha University and Chiang Mai University, and its most recent screening was at the Phimailongweek (พิมายฬองวีค) experimental arts festival in Korat.

Breaking the Cycle

Breaking the Cycle, directed by Aekaphong Saransate and Thanakrit Duangmaneeporn, is a fly-on-the-wall account of the Future Forward party, which was dissolved by the Constitutional Court in 2020. (Future Forward was founded as a progressive alternative to military dictatorship. The party came third in the 2019 election, after a wave of support for its charismatic leader, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, though he was disqualified as an MP by the Constitutional Court.)

The film begins in 2014 with Thanathorn’s determination to end the vicious cycle of military coups that has characterised Thailand’s modern political history. This mission gives the film its title, and Future Forward co-founder Piyabutr Saengkanokkul asks: “Why is Thailand stuck in this cycle of coups?” The documentary benefits from its extensive access to every senior figure within Future Forward. The directors were even able to film Thanathorn as he reacted to the guilty verdicts being delivered by the Constitutional Court.

The documentary ends with the caption “THE CYCLE CONTINUES”, which is sadly accurate: Future Forward’s successor, Move Forward, was dissolved by the Constitutional Court last year despite winning the 2023 election. The movement’s third incarnation, the People’s Party, endorsed Anutin Charnvirakul as Prime Minister this week, on the condition that he agreed to call a new election within four months.

Breaking the Cycle went on general release last year. It was later shown at the Thai Film Archive, as part of the Lost and Longing (แด่วันคืนที่สูญหาย) season. It was also screened at A.E.Y. Space in Songkla, and at the Bangsaen Film Festival (เทศกาลภาพยนตร์บางแสน) at Burapha University. It was part of the Hits Me Movies... One More Time programme at House Samyan in Bangkok, and earlier this year it was screened at Thammasat University and Chulalongkorn University.

The film begins in 2014 with Thanathorn’s determination to end the vicious cycle of military coups that has characterised Thailand’s modern political history. This mission gives the film its title, and Future Forward co-founder Piyabutr Saengkanokkul asks: “Why is Thailand stuck in this cycle of coups?” The documentary benefits from its extensive access to every senior figure within Future Forward. The directors were even able to film Thanathorn as he reacted to the guilty verdicts being delivered by the Constitutional Court.

The documentary ends with the caption “THE CYCLE CONTINUES”, which is sadly accurate: Future Forward’s successor, Move Forward, was dissolved by the Constitutional Court last year despite winning the 2023 election. The movement’s third incarnation, the People’s Party, endorsed Anutin Charnvirakul as Prime Minister this week, on the condition that he agreed to call a new election within four months.

Breaking the Cycle went on general release last year. It was later shown at the Thai Film Archive, as part of the Lost and Longing (แด่วันคืนที่สูญหาย) season. It was also screened at A.E.Y. Space in Songkla, and at the Bangsaen Film Festival (เทศกาลภาพยนตร์บางแสน) at Burapha University. It was part of the Hits Me Movies... One More Time programme at House Samyan in Bangkok, and earlier this year it was screened at Thammasat University and Chulalongkorn University.