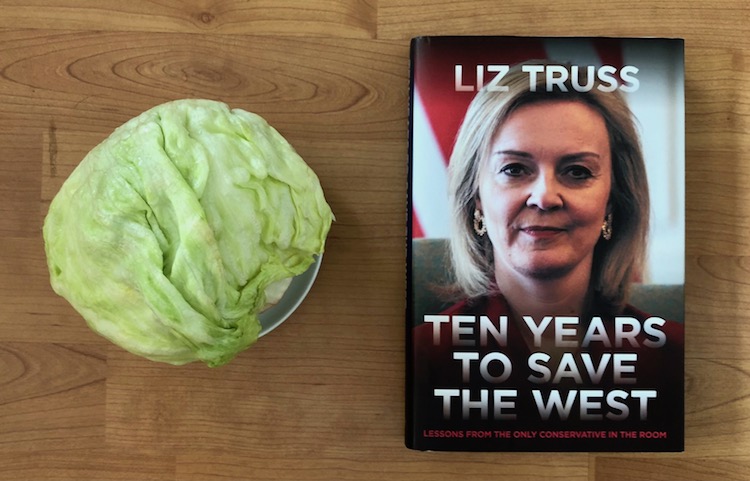

Liz Truss is, by a country mile, the UK’s shortest-serving prime minister in history, in office for only forty-nine days. The Economist magazine (15th October 2022) calculated that the Truss premiership had “roughly the shelf-life of a lettuce”, and the Daily Star newspaper proved that an actual lettuce could stay fresh throughout her entire term of office. (Harry Cole and James Healey wrote an excellent Truss biography, Out of the Blue.)

Truss has written a new memoir, Ten Years to Save the West: Lessons from the Only Conservative in the Room (subtitled Leading the Revolution Against Globalism, Socialism, and the Liberal Establishment in the US). But it’s not a conventional account of her premiership: “I do not see it as simply a chance to tell the detailed inside story of my time in government and justify every decision I made while I was there.” (Similarly, Theresa May wrote that her book was “not an attempt to justify certain decisions I made in office or to provide a detailed retelling of historical events.”)

Instead, Truss expresses her grievances about everything from the trivial (why would nobody help her book a haircut?) to the critical (why did economic institutions oppose her reckless fiscal policies?). Apparently, nothing was her fault: even though she asked Jeremy Hunt to become Chancellor before informing her close friend Kwasi Kwarteng that he was being sacked, she blames a leaker for revealing Hunt’s appointment on Twitter, where a shocked Kwarteng read about his replacement.

Summarising her premiership, Truss writes: “Things did not work out as I had hoped. My time in Downing Street was brief, and I did not have the chance to deliver the policies I had planned.” That first sentence brings to mind Hirohito’s famous understatement, when his country surrendered in 1945: “The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.”

Truss has written a new memoir, Ten Years to Save the West: Lessons from the Only Conservative in the Room (subtitled Leading the Revolution Against Globalism, Socialism, and the Liberal Establishment in the US). But it’s not a conventional account of her premiership: “I do not see it as simply a chance to tell the detailed inside story of my time in government and justify every decision I made while I was there.” (Similarly, Theresa May wrote that her book was “not an attempt to justify certain decisions I made in office or to provide a detailed retelling of historical events.”)

Instead, Truss expresses her grievances about everything from the trivial (why would nobody help her book a haircut?) to the critical (why did economic institutions oppose her reckless fiscal policies?). Apparently, nothing was her fault: even though she asked Jeremy Hunt to become Chancellor before informing her close friend Kwasi Kwarteng that he was being sacked, she blames a leaker for revealing Hunt’s appointment on Twitter, where a shocked Kwarteng read about his replacement.

Summarising her premiership, Truss writes: “Things did not work out as I had hoped. My time in Downing Street was brief, and I did not have the chance to deliver the policies I had planned.” That first sentence brings to mind Hirohito’s famous understatement, when his country surrendered in 1945: “The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.”