Alfred Barrett’s lonely hearts magazine The Link, founded in 1915, was certainly ahead of its time. It published personal ads, though as its masthead proudly proclaimed, they were “NOT MATRIMONIAL” in nature. So if people weren’t looking for a spouse, what could they be looking for...? The Metropolitan Police pondered that very question, after R.A. Bennett — editor of another magazine, the moralistic Truth — sent copies of The Link to Scotland Yard.

Bennett suspected that some of The Link’s classified ads were coded messages written by gay men. One example, which he underlined with a literal blue pencil, was by someone “anxious to correspond with friend. Must be same sex, affectionate, and amiable”. Homosexuality was illegal in Britain at the time, and the police seized not only copies of The Link but also letters sent to the box numbers advertised. Barrett was convicted of conspiracy to corrupt public morals in 1921, and sentenced to two years’ hard labour.

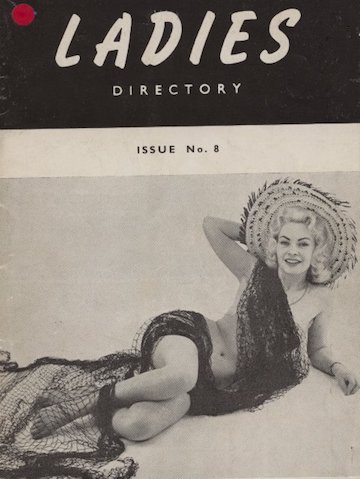

Forty years later, in 1961, another publisher was convicted of the same offence. Frederick Shaw’s Ladies Directory, founded in 1959, was a catalogue of ads placed by prostitutes (the equivalent of the ‘tart cards’ left in phone boxes). Shaw himself had sent his publication to the Director of Public Prosecutions, seeking guidance on its legality. He got his answer when the DPP charged him with conspiracy to corrupt public morals, and after his conviction he served nine months in prison. The charge — which set a legal precedent — related specifically to no. 7–10 of the Ladies Directory. (My copy of no. 8 is an undated and unpaginated A5 booklet.)

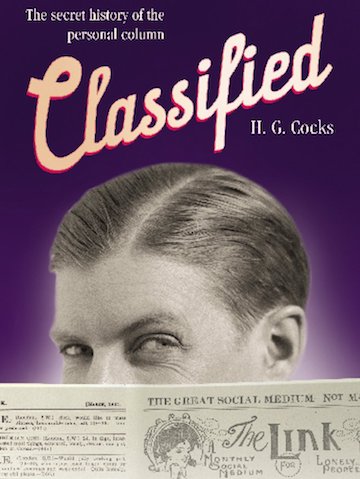

In 1965, Way Out led a revival of the lonely hearts magazine, and soon inspired imitators such as Exit and numerous others. In his authoritative Encyclopedia of Censorship, Jonathon Green noted that these titles “were not prosecuted, and more respectable magazines began to run lonely hearts columns that might have been indictable in earlier years.” H.G. Cocks, however, in his book Classified: The Secret History of the Personal Column, demonstrates that these titles were indeed prosecuted for conspiracy to corrupt public morals: “The way the police in Britain investigated smalltime magazines like Exit and Way Out while their American counterparts merely shrugged as their own swinging industry exploded, tells us everything about the differences between the two countries.” (Classified’s coverage of the investigation into Exit and Way Out sets it apart from other books on censorship in Britain.)

The last major UK conviction for consiracy to corrupt public morals came in 1970, when three publishers of the underground magazine International Times received suspended sentences. In 1969 (issues 51–56), IT published a column of gay personal ads (Males), and this gave the Metropolitan Police the excuse they needed to prosecute the magazine, after several previous speculative raids on its offices. In an echo of the investigation into The Link fifty years earlier, and notwithstanding the legalisation of homosexuality in 1967, the police seized hundreds of letters sent in reply to the ads. The editors of a more famous underground title, Oz, were acquitted of conspiracy to corrupt public morals in 1971, though after a prolonged trial they were found guilty of obscenity (a verdict later overturned on appeal).

Bennett suspected that some of The Link’s classified ads were coded messages written by gay men. One example, which he underlined with a literal blue pencil, was by someone “anxious to correspond with friend. Must be same sex, affectionate, and amiable”. Homosexuality was illegal in Britain at the time, and the police seized not only copies of The Link but also letters sent to the box numbers advertised. Barrett was convicted of conspiracy to corrupt public morals in 1921, and sentenced to two years’ hard labour.

Forty years later, in 1961, another publisher was convicted of the same offence. Frederick Shaw’s Ladies Directory, founded in 1959, was a catalogue of ads placed by prostitutes (the equivalent of the ‘tart cards’ left in phone boxes). Shaw himself had sent his publication to the Director of Public Prosecutions, seeking guidance on its legality. He got his answer when the DPP charged him with conspiracy to corrupt public morals, and after his conviction he served nine months in prison. The charge — which set a legal precedent — related specifically to no. 7–10 of the Ladies Directory. (My copy of no. 8 is an undated and unpaginated A5 booklet.)

In 1965, Way Out led a revival of the lonely hearts magazine, and soon inspired imitators such as Exit and numerous others. In his authoritative Encyclopedia of Censorship, Jonathon Green noted that these titles “were not prosecuted, and more respectable magazines began to run lonely hearts columns that might have been indictable in earlier years.” H.G. Cocks, however, in his book Classified: The Secret History of the Personal Column, demonstrates that these titles were indeed prosecuted for conspiracy to corrupt public morals: “The way the police in Britain investigated smalltime magazines like Exit and Way Out while their American counterparts merely shrugged as their own swinging industry exploded, tells us everything about the differences between the two countries.” (Classified’s coverage of the investigation into Exit and Way Out sets it apart from other books on censorship in Britain.)

The last major UK conviction for consiracy to corrupt public morals came in 1970, when three publishers of the underground magazine International Times received suspended sentences. In 1969 (issues 51–56), IT published a column of gay personal ads (Males), and this gave the Metropolitan Police the excuse they needed to prosecute the magazine, after several previous speculative raids on its offices. In an echo of the investigation into The Link fifty years earlier, and notwithstanding the legalisation of homosexuality in 1967, the police seized hundreds of letters sent in reply to the ads. The editors of a more famous underground title, Oz, were acquitted of conspiracy to corrupt public morals in 1971, though after a prolonged trial they were found guilty of obscenity (a verdict later overturned on appeal).

Although corrupting public morals is now an outdated offence in the UK, it remains a serious crime in countries such as Egypt. I 2017, Egyptian television presenter Doaa Salah was sentenced to three years in prison for outraging public decency, after she advocated single motherhood on her variety TV show مع دودي (‘with Doaa’). In an episode broadcast by Al Nahar on 28th July 2017, she delivered a tongue-in-cheek monologue recommending women to visit sperm banks, become pregnant before marriage, or enter into short-term marriages of convenience.

Similarly, another Egyptian TV presenter was jailed for one year in 2019, after being found guilty of inciting immorality. Mohamed al-Ghiety’s satellite TV talk show صح النوم (‘wake up’), featured a gay man discussing his sex life in an episode transmitted on 5th August 2018. (The man&rsuo;s face was blurred to disguise his identity.) The broadcaster, LTC TV, was suspended for a fortnight after the programme was aired.