After Nottapon Boonprakob submitted his documentary Come and See (เอหิปัสสิโก) to the Thai censorship board, they telephoned him and explained that some board members had reservations about it. Would he mind if they rejected the film, they asked. Naturally, he did mind, so they invited him to a meeting. After the phone call, the Thai Film Director Association publicised the case online, and the stage was set for another Thai film censorship controversy. However, when Nottapon met the censors on 10th March, they told him that there was no problem, and the film was passed uncut with a universal ‘G’ rating.

It’s likely that the censors capitulated as a result of the publicity generated by their rather naïve phone call. The earlier case of Nontawat Numbenchapol’s Boundary (ฟ้าต่ำแผ่นดินสูง) was very similar: that film’s ban was swiftly reversed following online publicity about it. (Nontawat’s film was subject to a token cut, imposed to save the face of the censorship board who had originally banned it.)

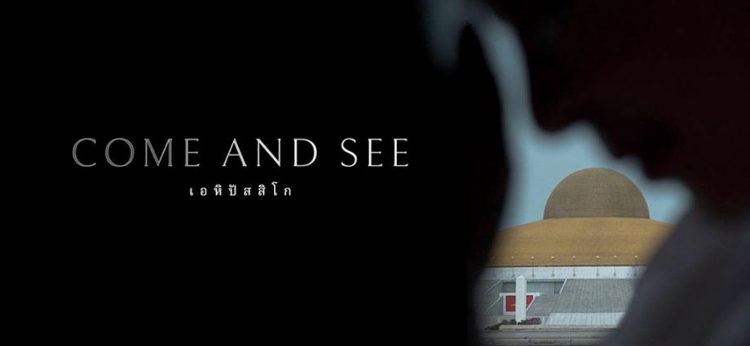

Come and See and Boundary are both documentaries about controversial temples. In Boundary’s case, the controversy was territorial, with Thailand and Cambodia both claiming ownership of the disputed Preah Vihear on the border between the two countries. Come and See, on the other hand, examines the practices of the Wat Phra Dhammakaya temple complex (in Pathum Thani province, near Bangkok) and its former abbot, Dhammajayo, who has long been suspected of money laundering.

Dhammakaya is a Buddhist sect recognised by the Sangha Supreme Council, though it closely resembles a cult. Dhammakaya supporters are encouraged to make large financial donations in return for promises of salvation, and thousands of followers have given their savings to the temple. (Come and See interviews both current devotees and disaffected former members.) After Dhammajayo was accused of corruption, a declaration of his innocence was added to the temple’s morning prayers. (The film shows temple visitors reciting this like a mantra.)

The Dhammakaya complex itself is only twenty years old, and its design is inherently cinematic. The enormous Cetiya temple resembles a golden UFO, and temple ceremonies are conducted on an epic scale, with tens of thousands of monks and worshippers arranged with geometric precision. The temple cooperated with Nottapon, though his access was limited; Come and See doesn’t investigate the allegations against Dhammajayo, though it does provide extensive coverage of the 2016 DSI raid on the temple and Dhammajayo’s subsequent disappearance.

It’s likely that the censors capitulated as a result of the publicity generated by their rather naïve phone call. The earlier case of Nontawat Numbenchapol’s Boundary (ฟ้าต่ำแผ่นดินสูง) was very similar: that film’s ban was swiftly reversed following online publicity about it. (Nontawat’s film was subject to a token cut, imposed to save the face of the censorship board who had originally banned it.)

Come and See and Boundary are both documentaries about controversial temples. In Boundary’s case, the controversy was territorial, with Thailand and Cambodia both claiming ownership of the disputed Preah Vihear on the border between the two countries. Come and See, on the other hand, examines the practices of the Wat Phra Dhammakaya temple complex (in Pathum Thani province, near Bangkok) and its former abbot, Dhammajayo, who has long been suspected of money laundering.

Dhammakaya is a Buddhist sect recognised by the Sangha Supreme Council, though it closely resembles a cult. Dhammakaya supporters are encouraged to make large financial donations in return for promises of salvation, and thousands of followers have given their savings to the temple. (Come and See interviews both current devotees and disaffected former members.) After Dhammajayo was accused of corruption, a declaration of his innocence was added to the temple’s morning prayers. (The film shows temple visitors reciting this like a mantra.)

The Dhammakaya complex itself is only twenty years old, and its design is inherently cinematic. The enormous Cetiya temple resembles a golden UFO, and temple ceremonies are conducted on an epic scale, with tens of thousands of monks and worshippers arranged with geometric precision. The temple cooperated with Nottapon, though his access was limited; Come and See doesn’t investigate the allegations against Dhammajayo, though it does provide extensive coverage of the 2016 DSI raid on the temple and Dhammajayo’s subsequent disappearance.