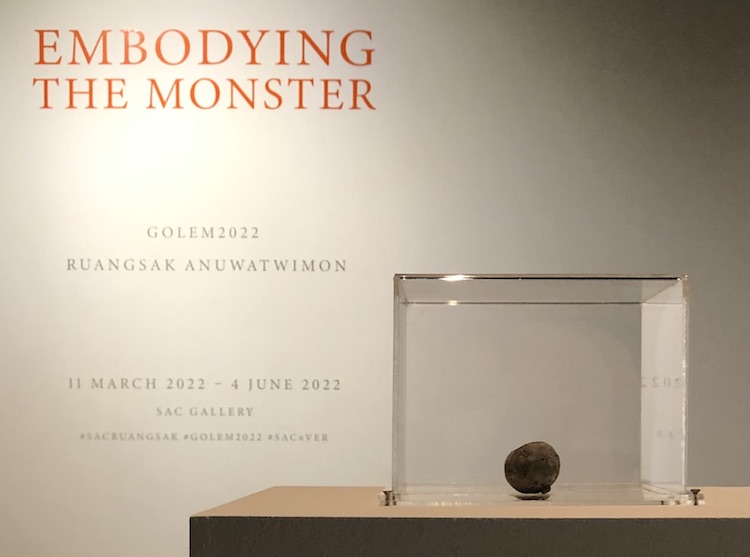

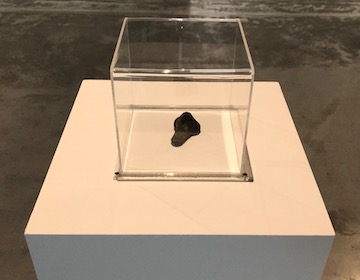

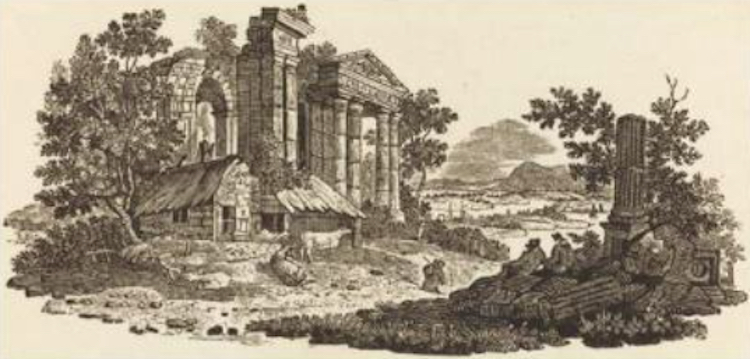

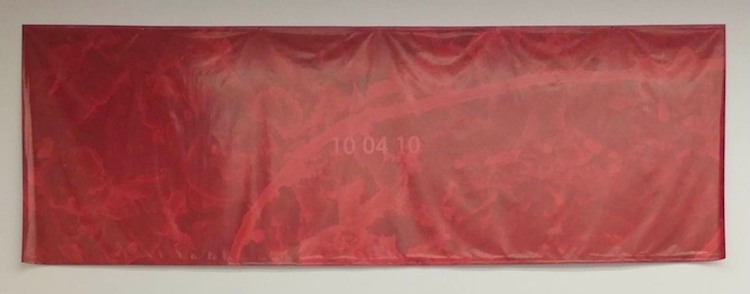

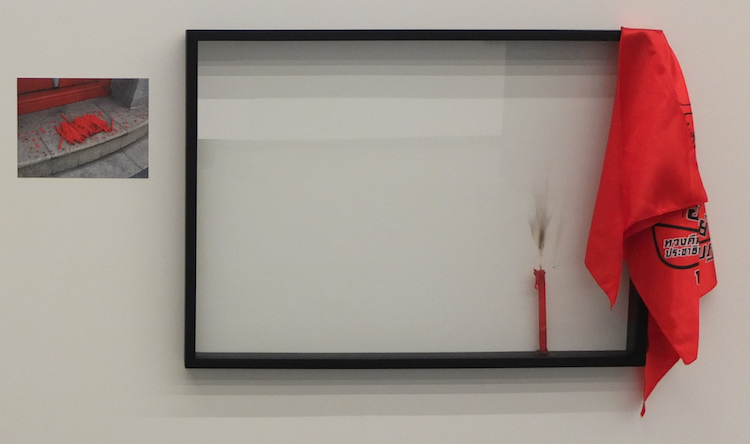

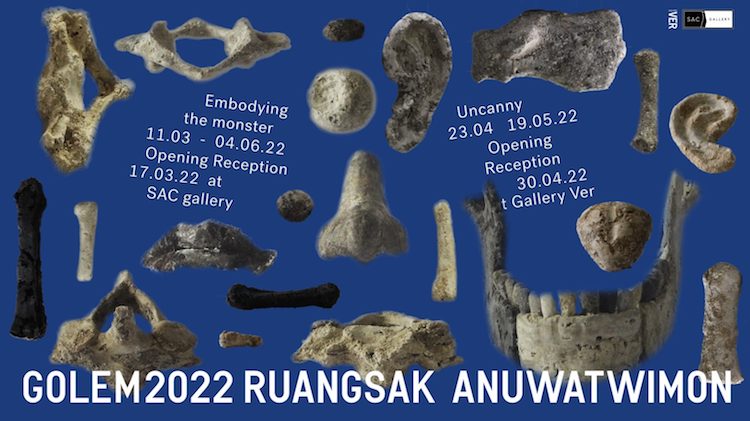

Uncanny, the companion exhibition to Ruangsak Anuwatwimon’s Embodying the Monster, opened today in Bangkok. Both are part of his ongoing Golem 2022 project, for which he is gradually creating the bones and organs of a mythical golem figure, constructed from the ashes of dead animals and plants. The species he has cremated have all been affected by human behaviour, and his golem therefore literally and figuratively embodies the relationship between humanity and nature.

Uncanny reveals the process by which the golem is being brought to life. The gallery has become a contemporary Frankenstein’s laboratory, with a 3D printer manufacturing body parts from ashes. Specimens of endangered animals, the raw materials for Ruangsak’s monster, are displayed in jars. The finished products are carefully catalogued, ready to be assembled.

Uncanny reveals the process by which the golem is being brought to life. The gallery has become a contemporary Frankenstein’s laboratory, with a 3D printer manufacturing body parts from ashes. Specimens of endangered animals, the raw materials for Ruangsak’s monster, are displayed in jars. The finished products are carefully catalogued, ready to be assembled.

The assembly and articulation of the skeleton will take place in four stages, as performance art, on 27th April and 6th, 27th, and 28th May. Uncanny runs at Gallery VER until 19th May. Embodying the Monster is at SAC Gallery, also in Bangkok, until 5th June. Ruangsak has previously created heart sculptures—Transformations and the Ash Heart Project—from the ashes of various species, including humans.