Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s new film Memoria will have its Thai premiere on 24th February. The screening at Bangkok’s SF World cinema will be followed by a post-screening discussion with Apichatpong and actor Tilda Swinton. The following day, Apichatpong will also be present to discuss Memoria when it’s shown at the Thai Film Archive in Salaya, before it goes on general release on 3rd March.

On 26th February, the Film Archive will host a masterclass by Apichatpong, Memory of Filmmaking, moderated by Sompot Chidgasornpongse (a key member of his Kick the Machine production team) and Nottapon Boonprakob (director of Come and See/เอหิปัสสิโก). Apichatpong has previously given similar presentations at the Film Archive—ตัวตน โดย ตัวงาน (‘self-expression through work’) in 2011—and elsewhere: What Is Not Visible Is Not Invisible at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre in 2017, Indy Spirit Project at SF Cinema City in 2010, and Tomyam Pladib (ต้มยำปลาดิบ) at the Jim Thompson Art Center in 2008.

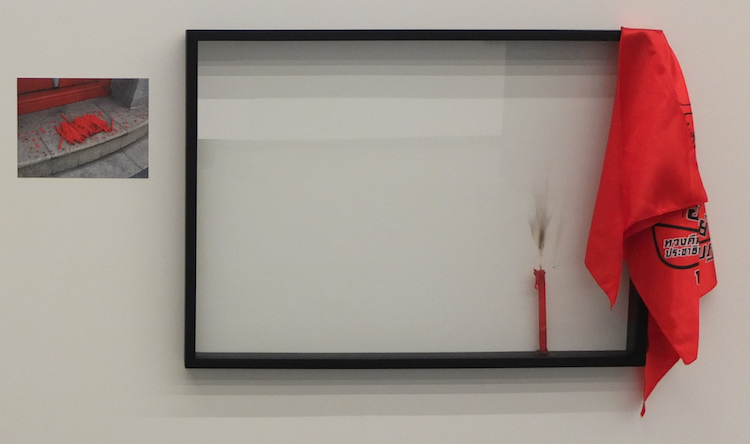

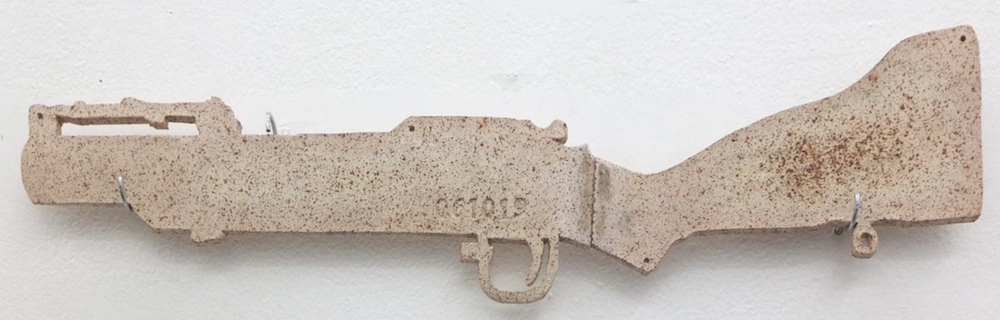

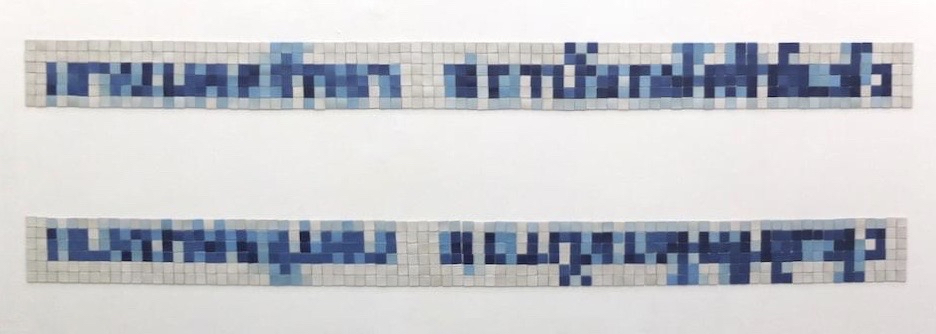

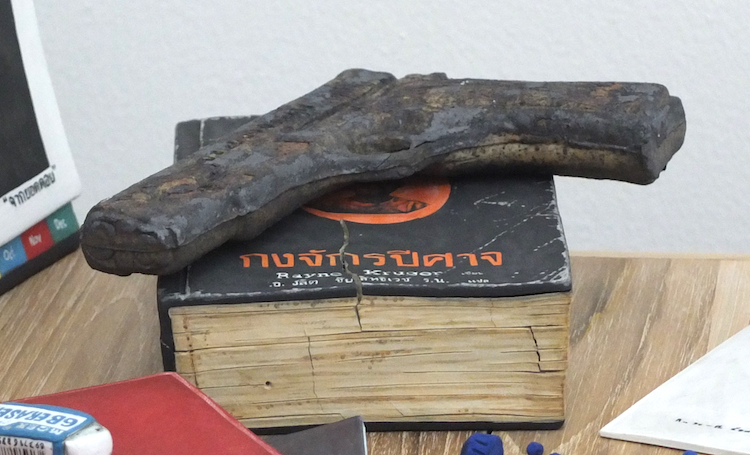

Memoria received its world premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Jury Prize. The second phase of Apichatpong’s exhibition A Minor History (ประวัติศาสตร์กระจ้อยร่อย ภาคสอง)—subtitled Beautiful Things (สิ่งสวยงาม)—opened at 100 Tonson Foundation in Bangkok on 18th February, and runs until 10th April.

On 26th February, the Film Archive will host a masterclass by Apichatpong, Memory of Filmmaking, moderated by Sompot Chidgasornpongse (a key member of his Kick the Machine production team) and Nottapon Boonprakob (director of Come and See/เอหิปัสสิโก). Apichatpong has previously given similar presentations at the Film Archive—ตัวตน โดย ตัวงาน (‘self-expression through work’) in 2011—and elsewhere: What Is Not Visible Is Not Invisible at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre in 2017, Indy Spirit Project at SF Cinema City in 2010, and Tomyam Pladib (ต้มยำปลาดิบ) at the Jim Thompson Art Center in 2008.

Memoria received its world premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Jury Prize. The second phase of Apichatpong’s exhibition A Minor History (ประวัติศาสตร์กระจ้อยร่อย ภาคสอง)—subtitled Beautiful Things (สิ่งสวยงาม)—opened at 100 Tonson Foundation in Bangkok on 18th February, and runs until 10th April.